Techno Activate

06.01.2021

Since the Summer of 2019 Techno Activate have been mapping, uncovering and researching the underground techno archive at MayDay Rooms.

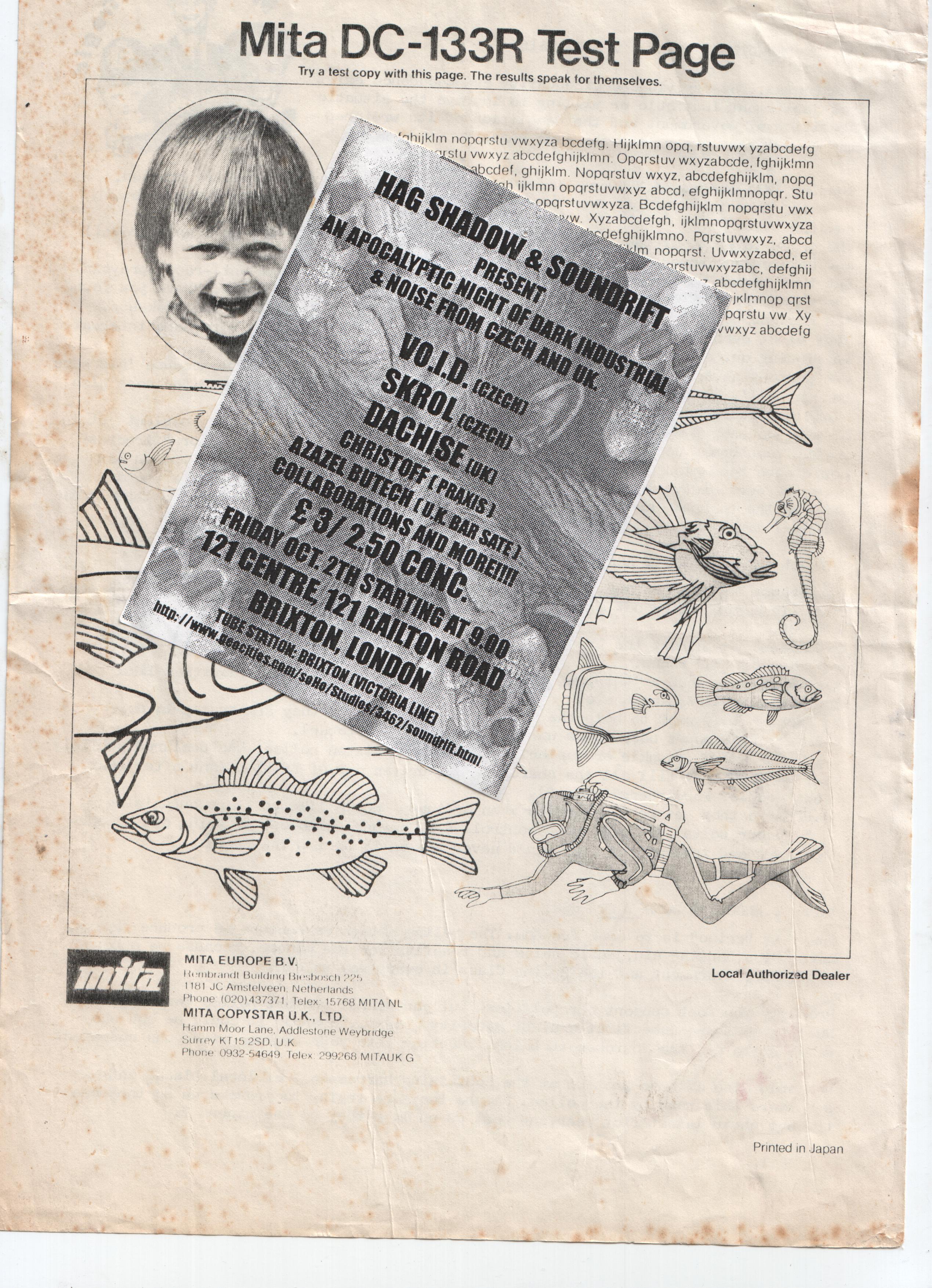

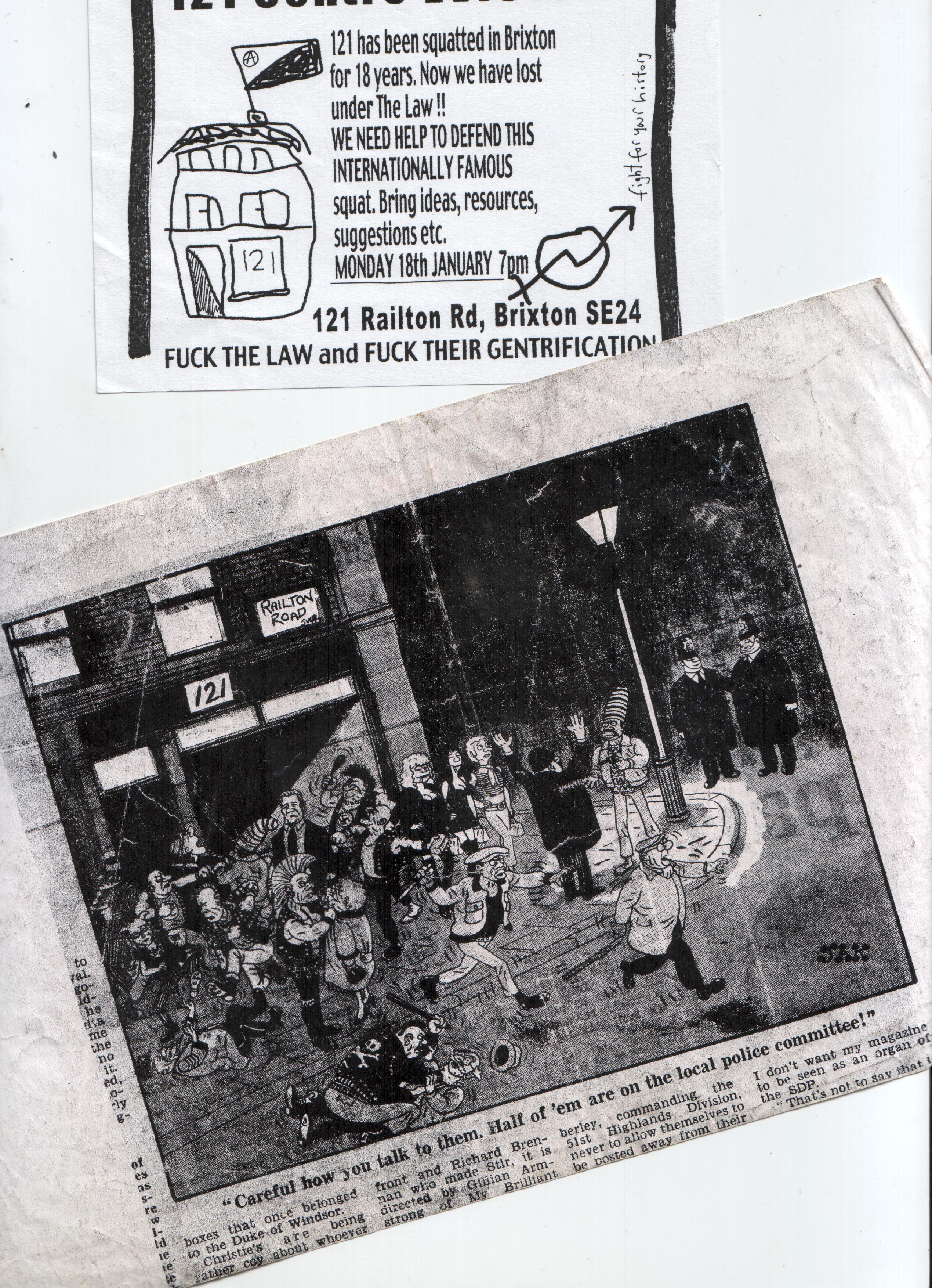

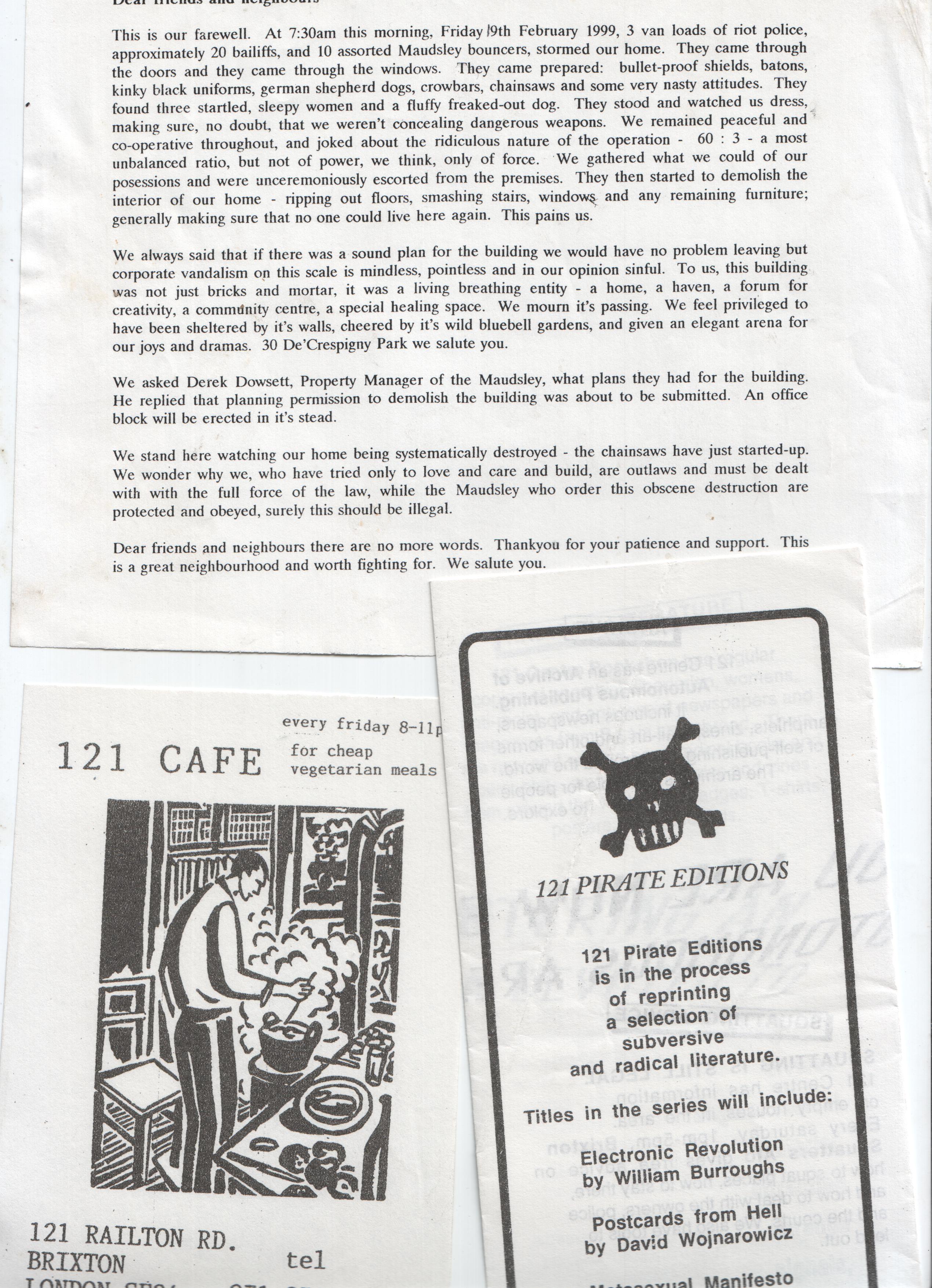

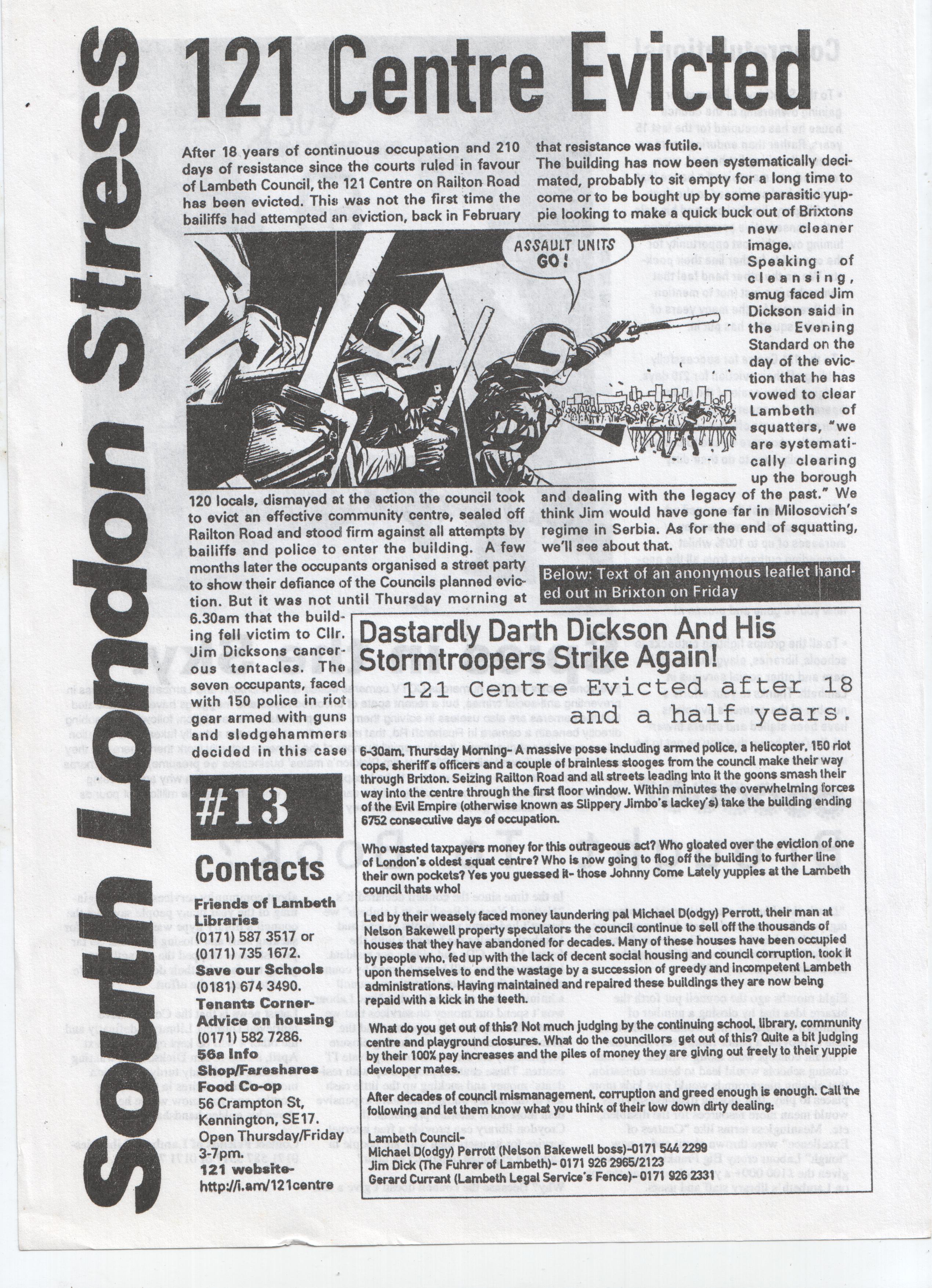

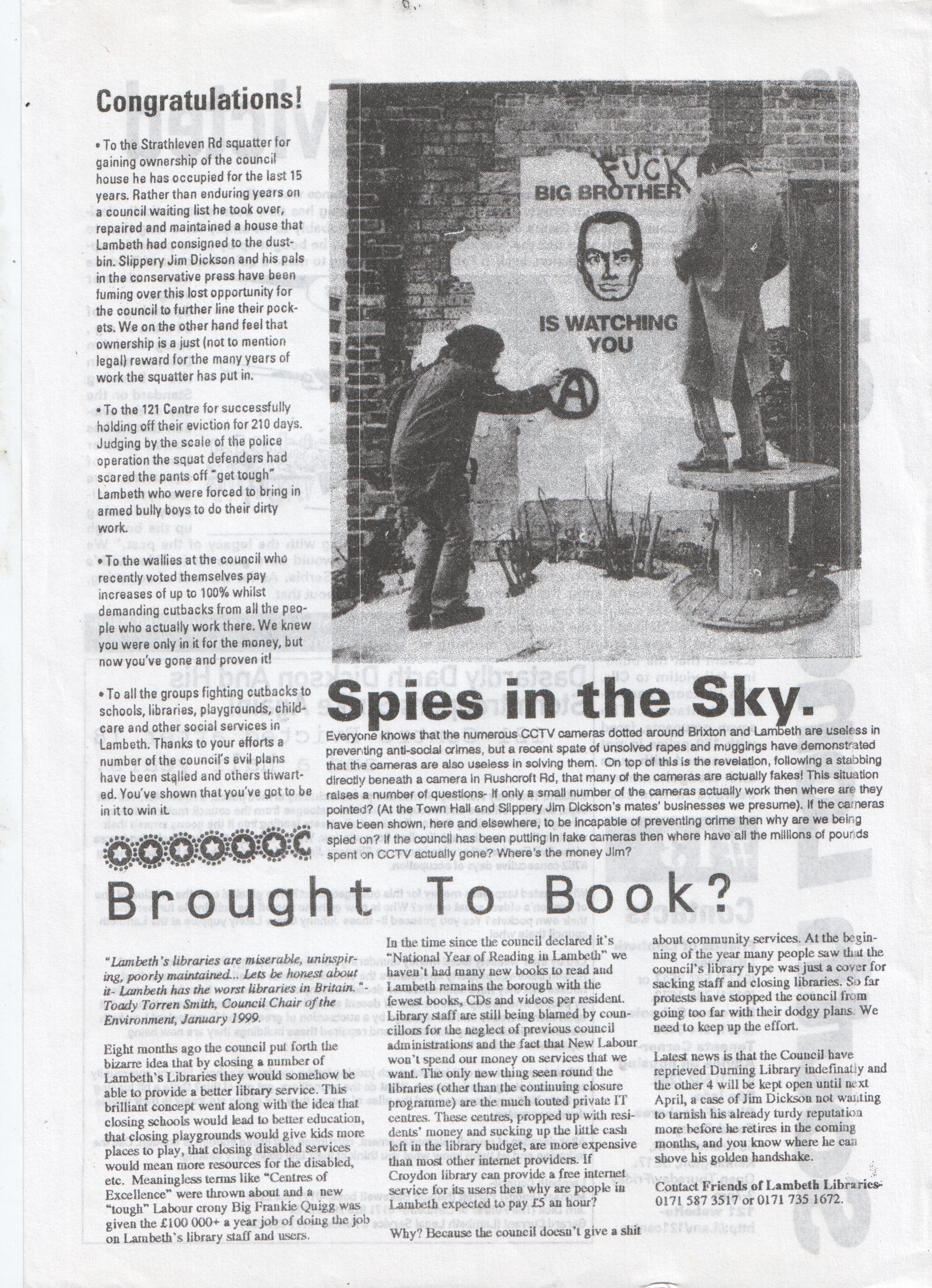

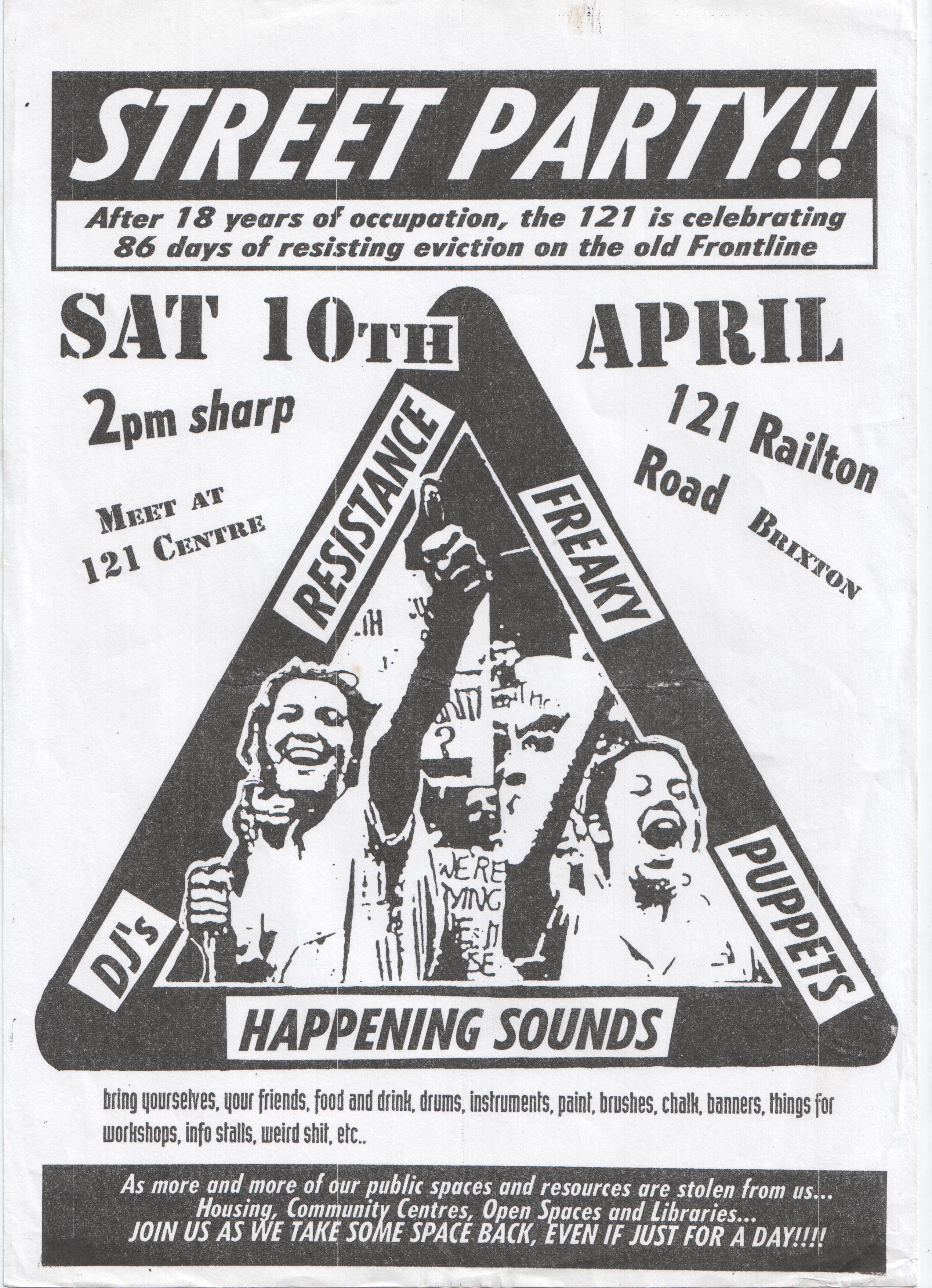

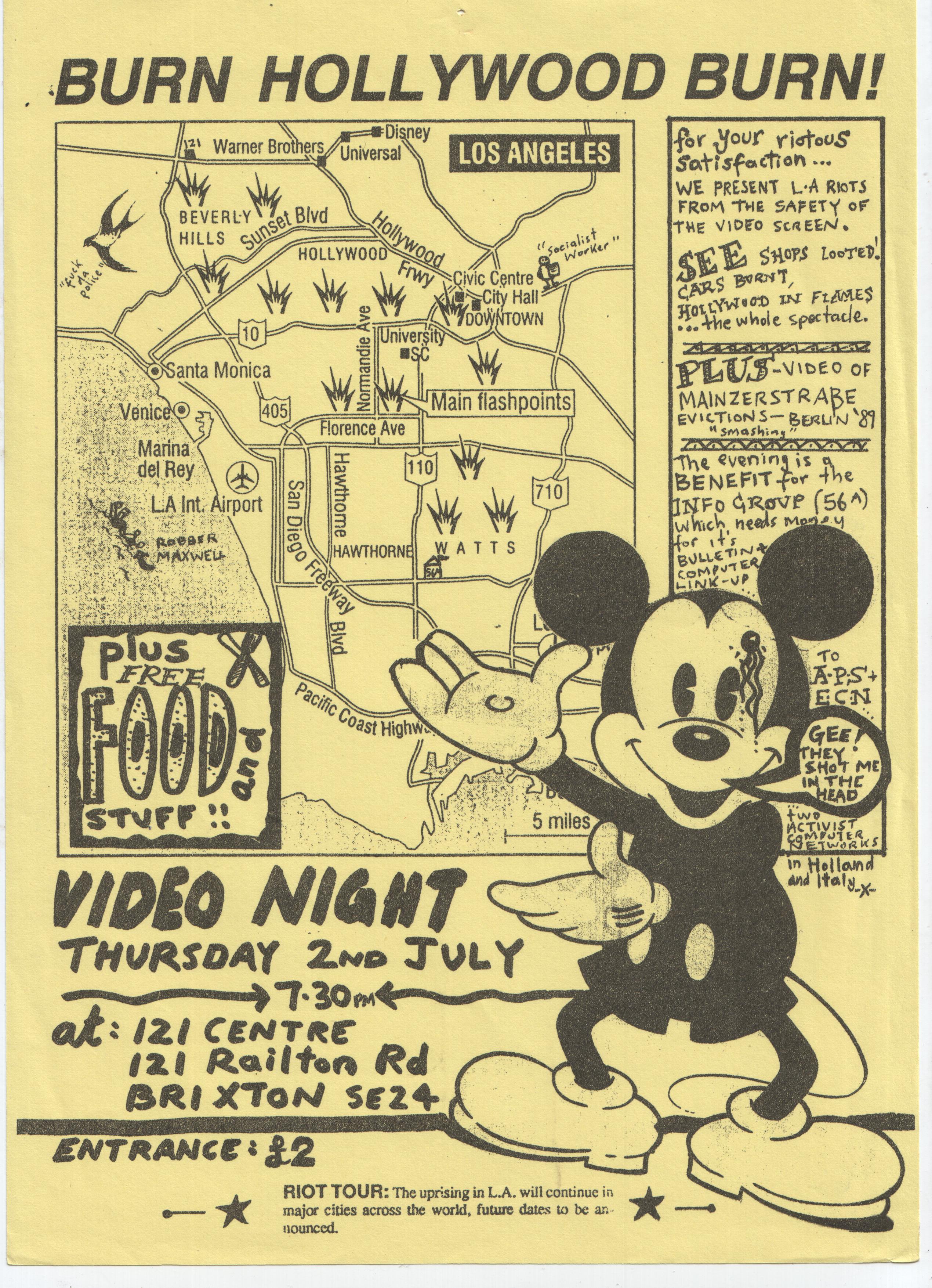

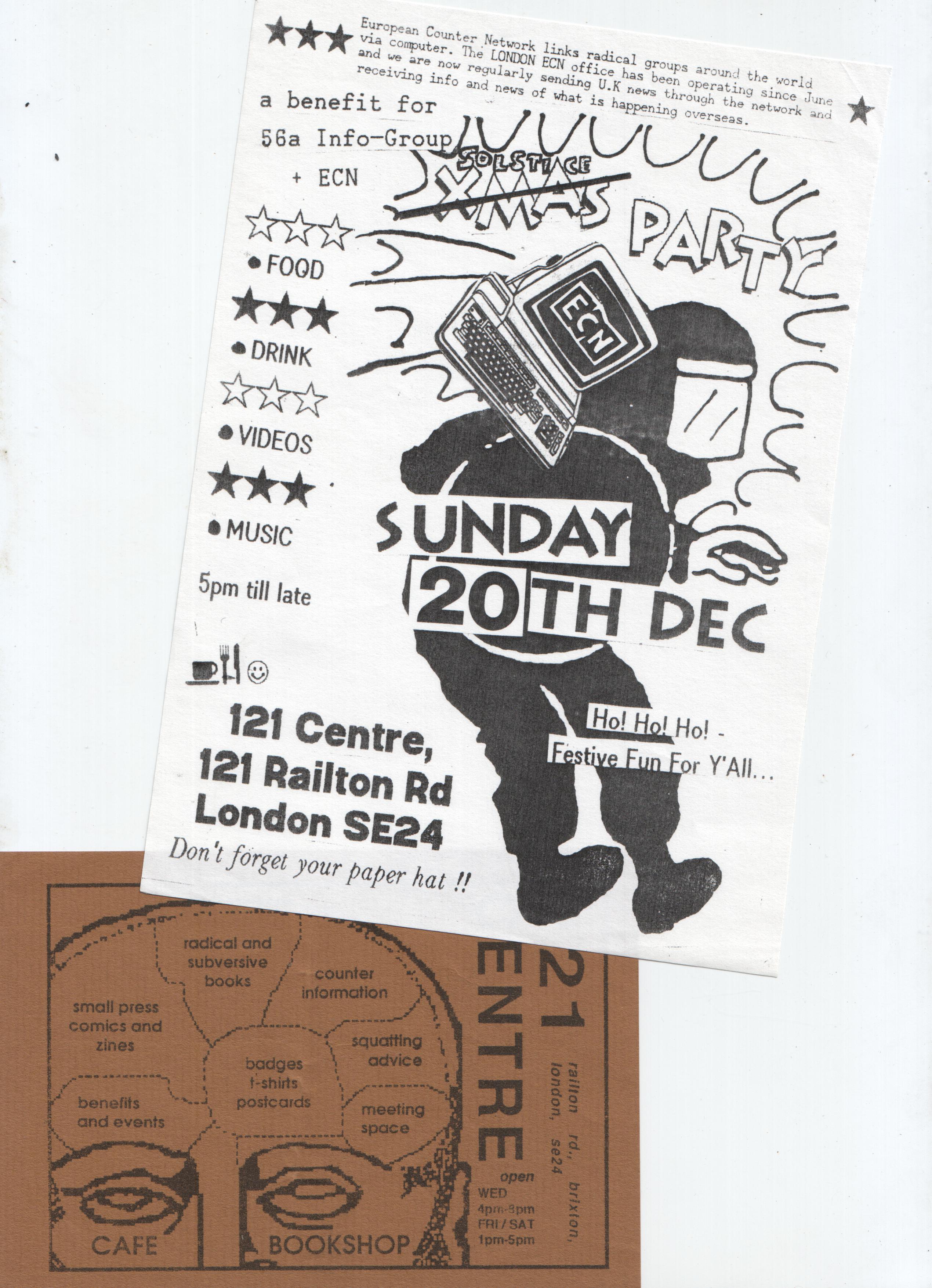

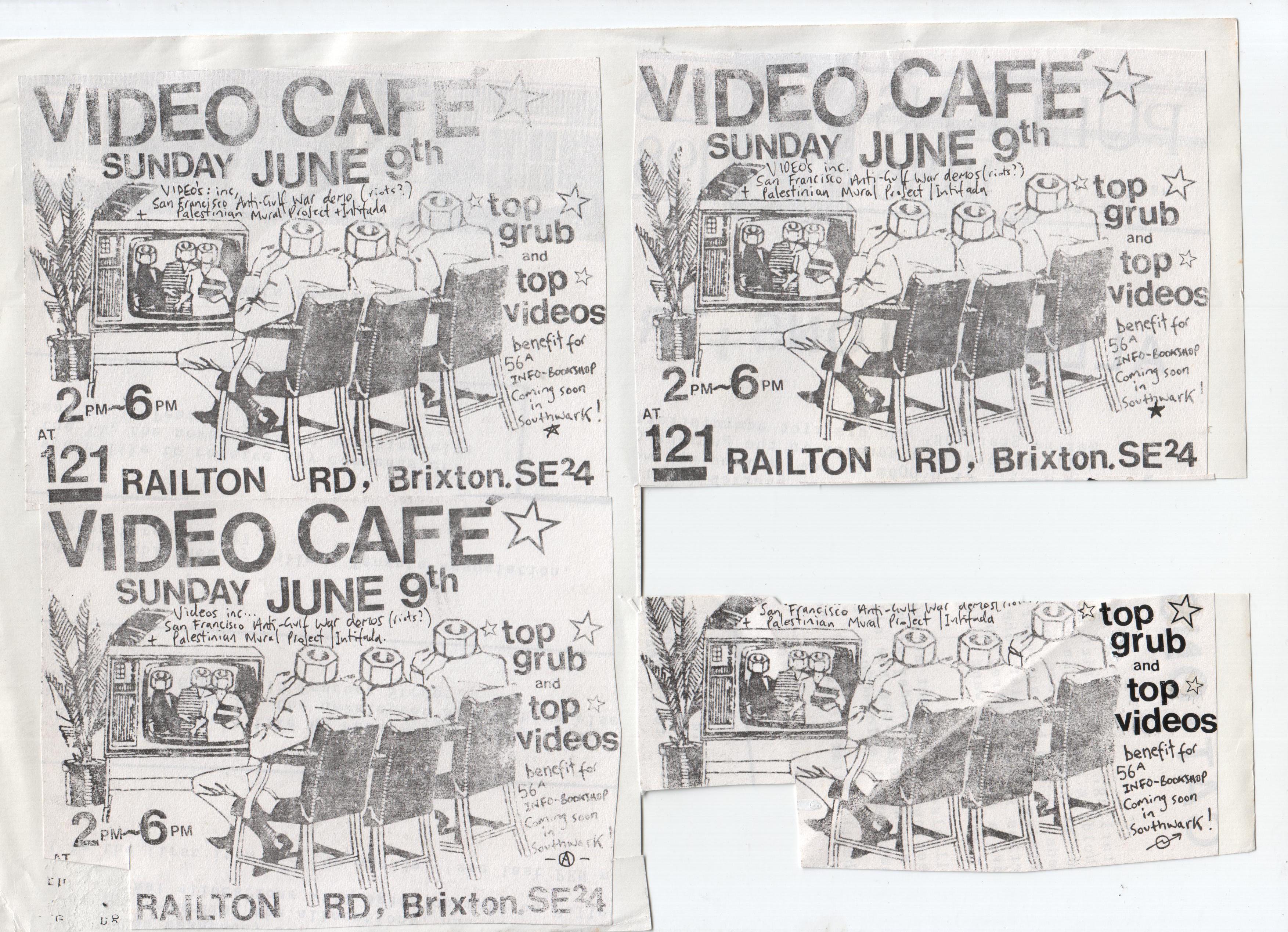

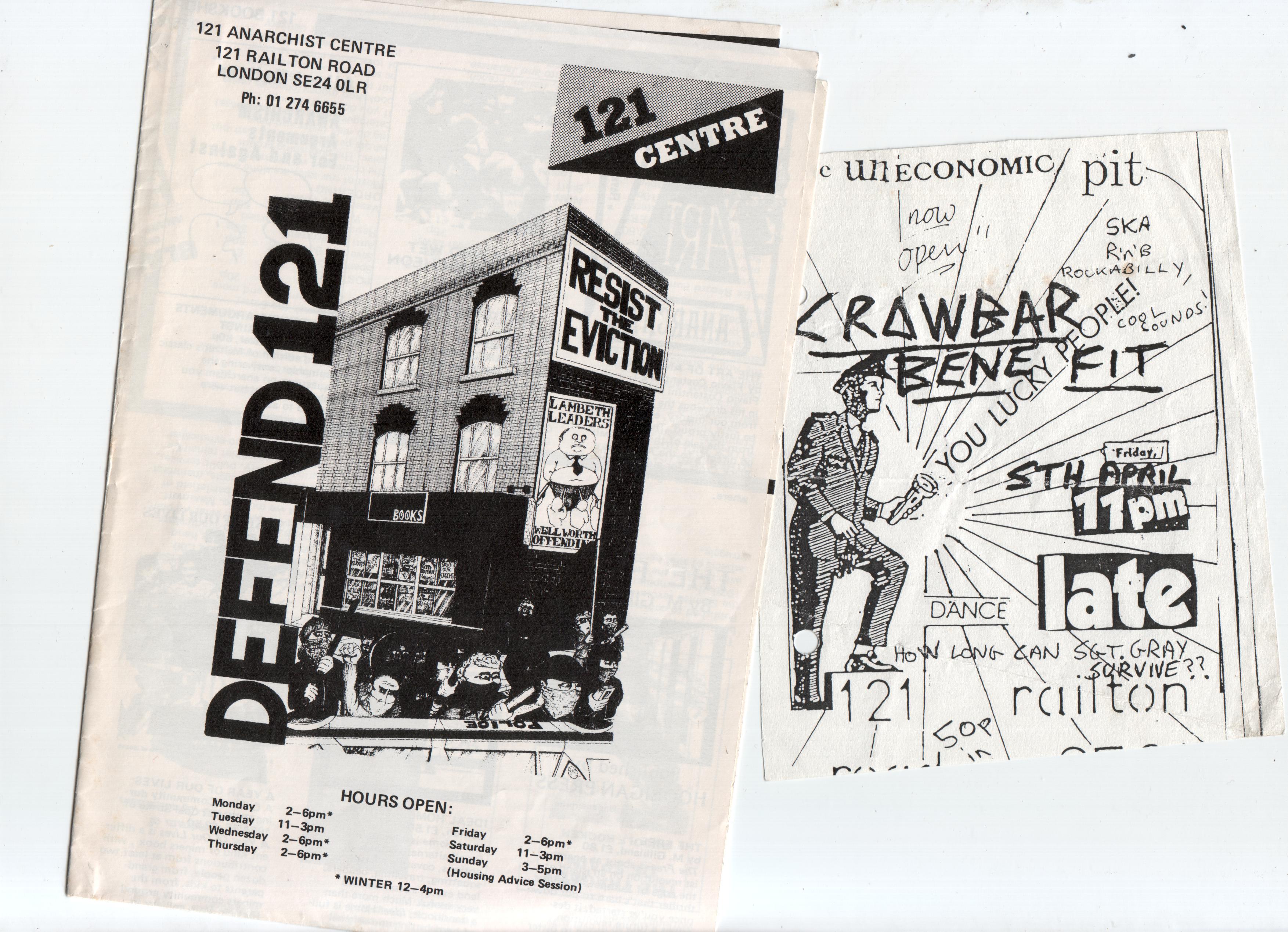

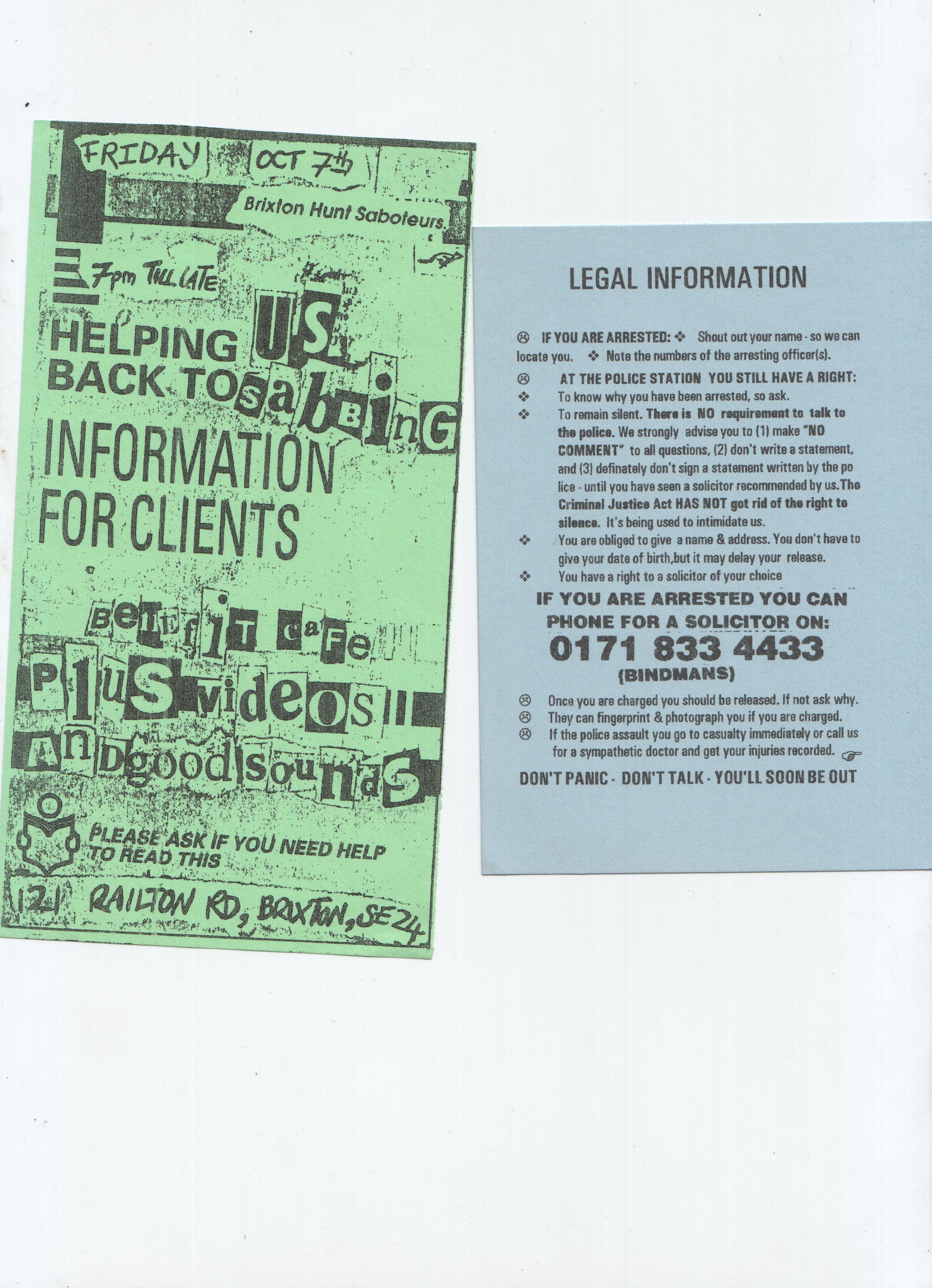

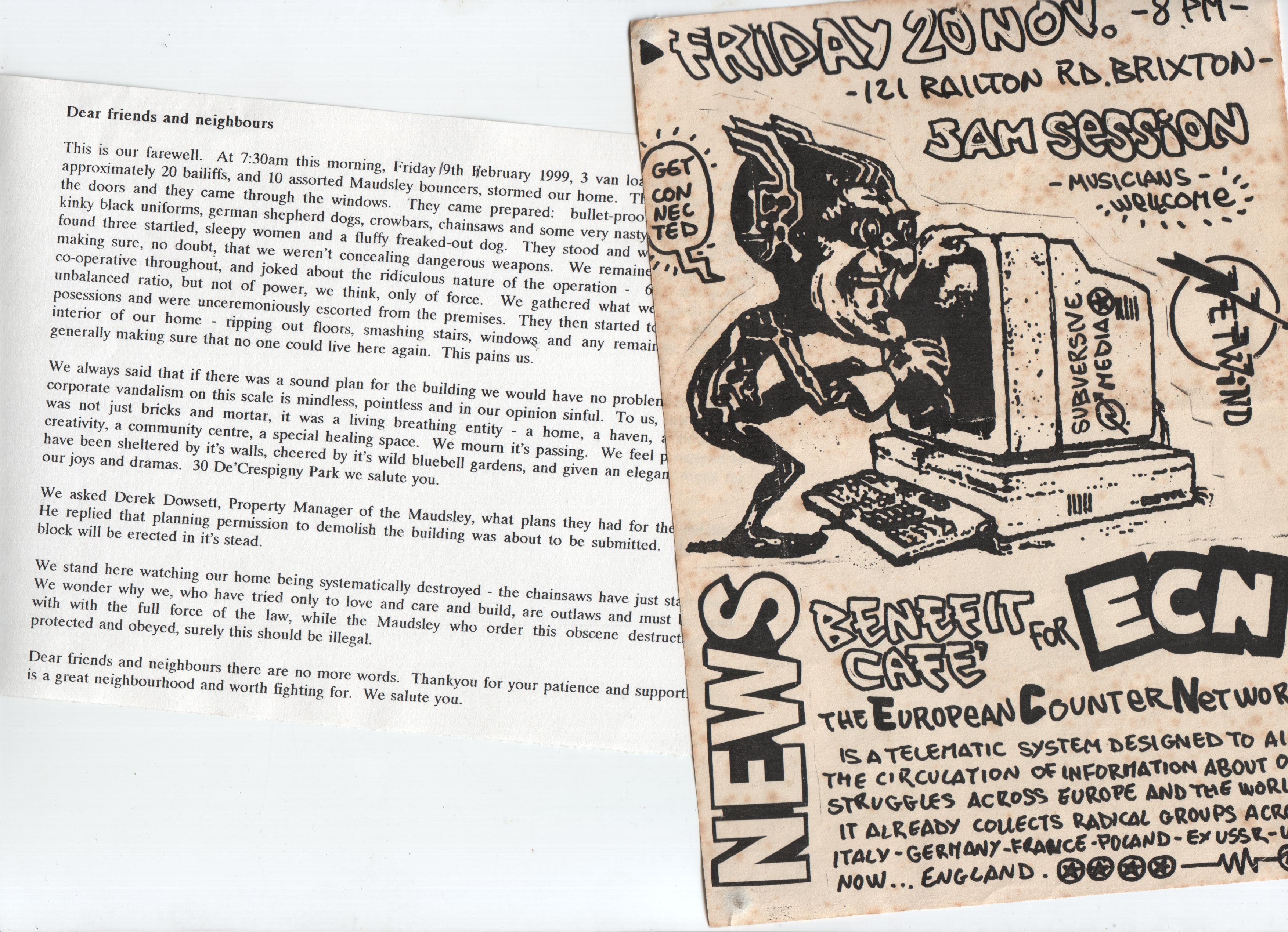

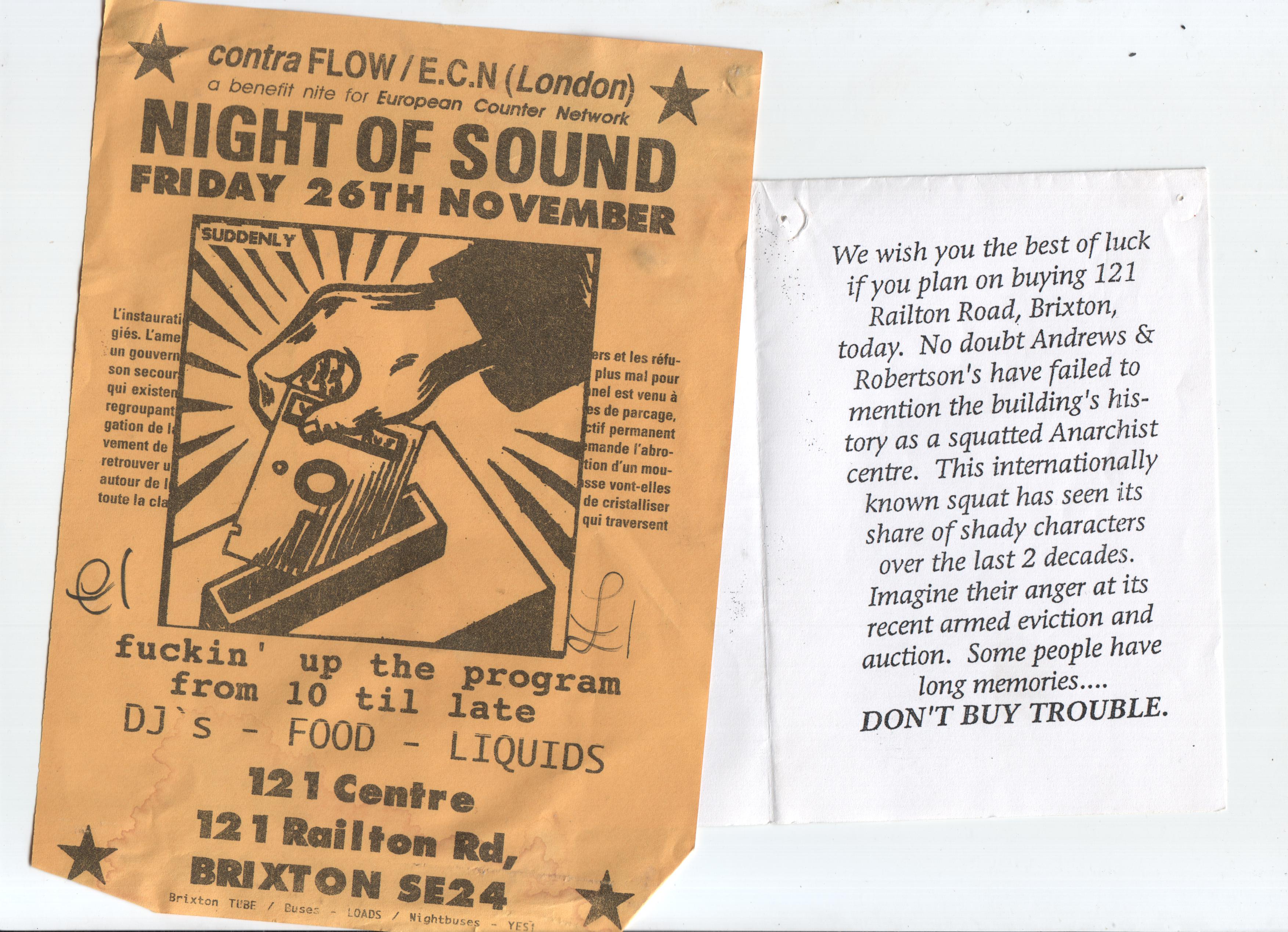

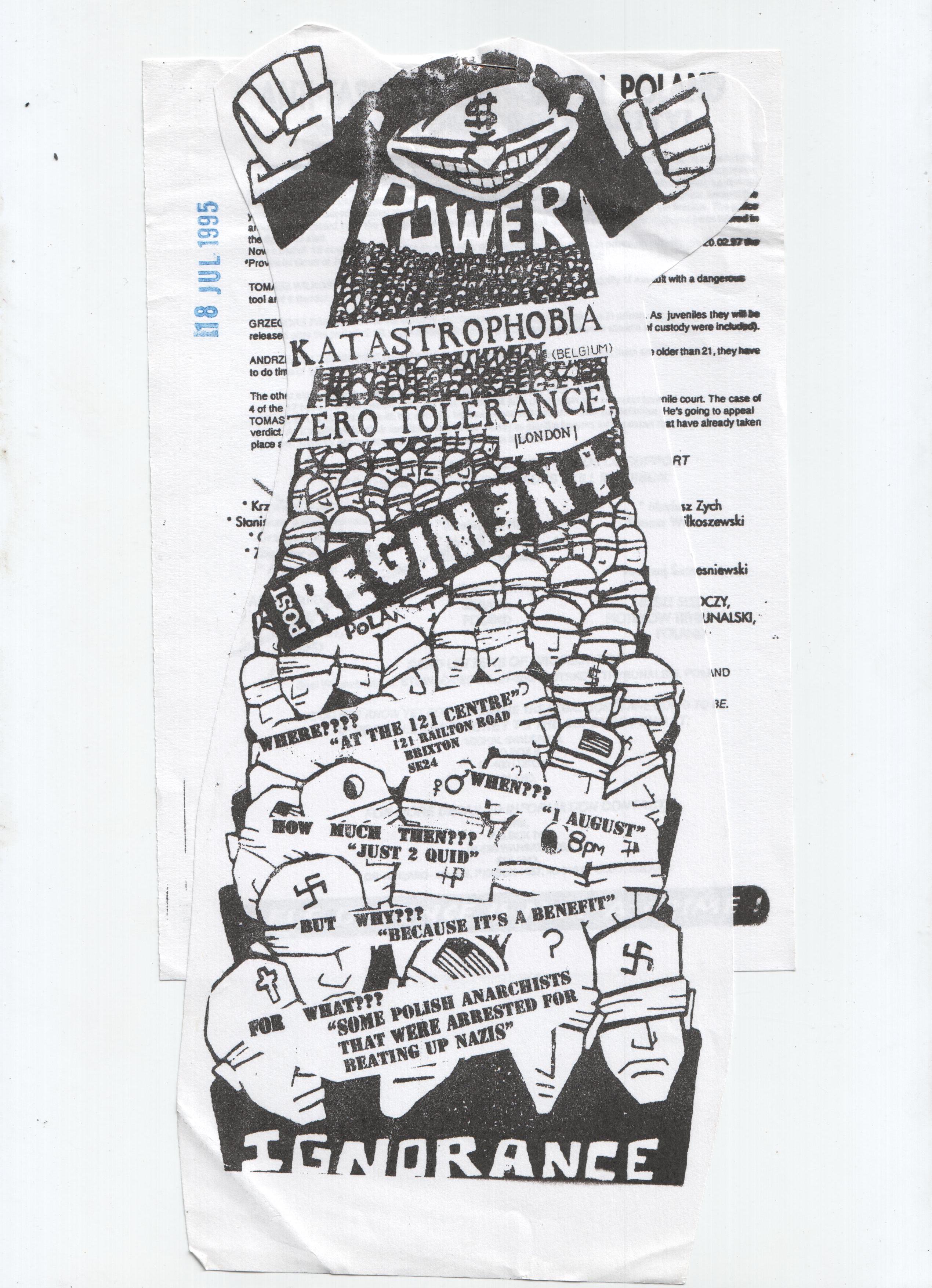

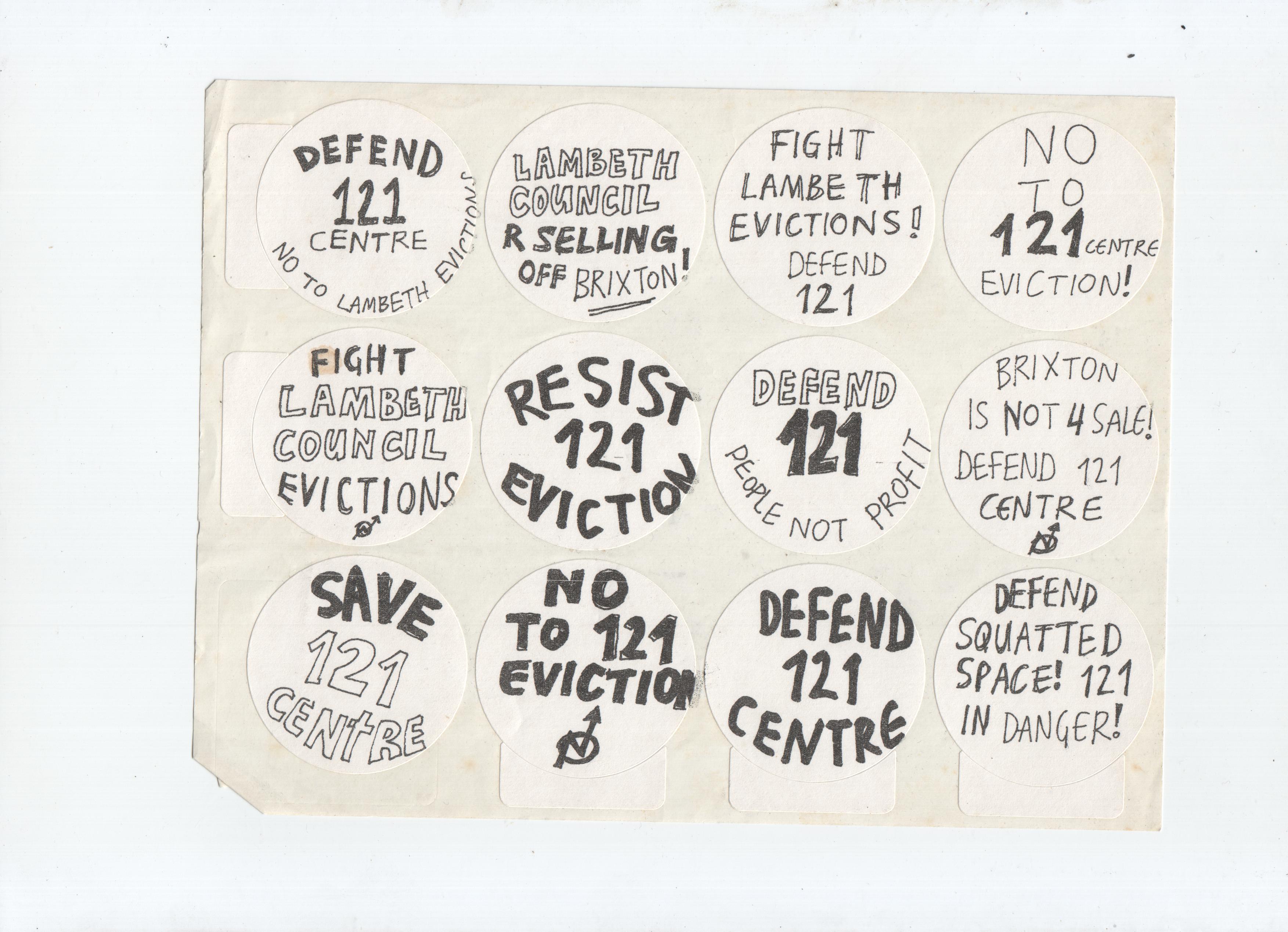

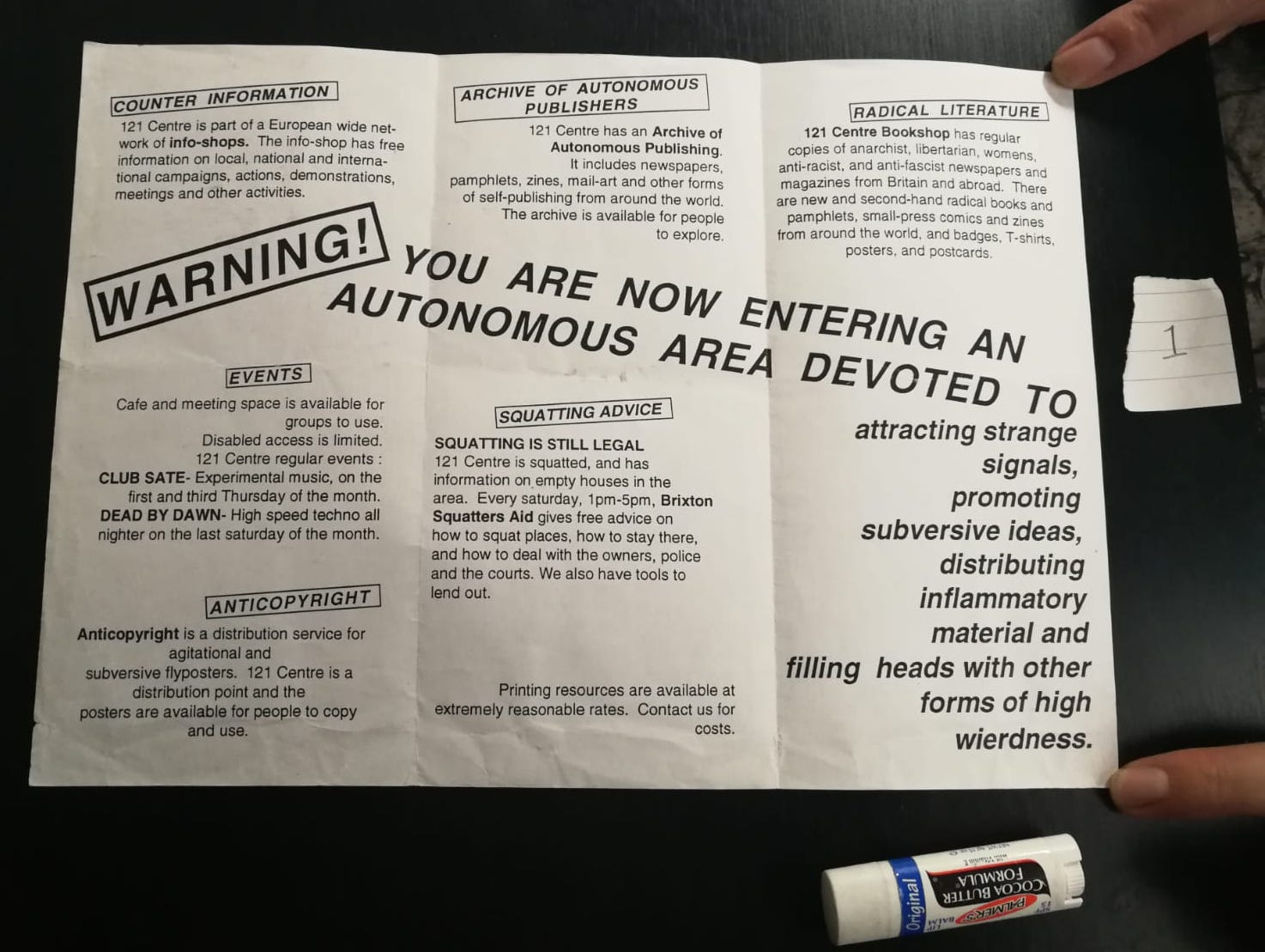

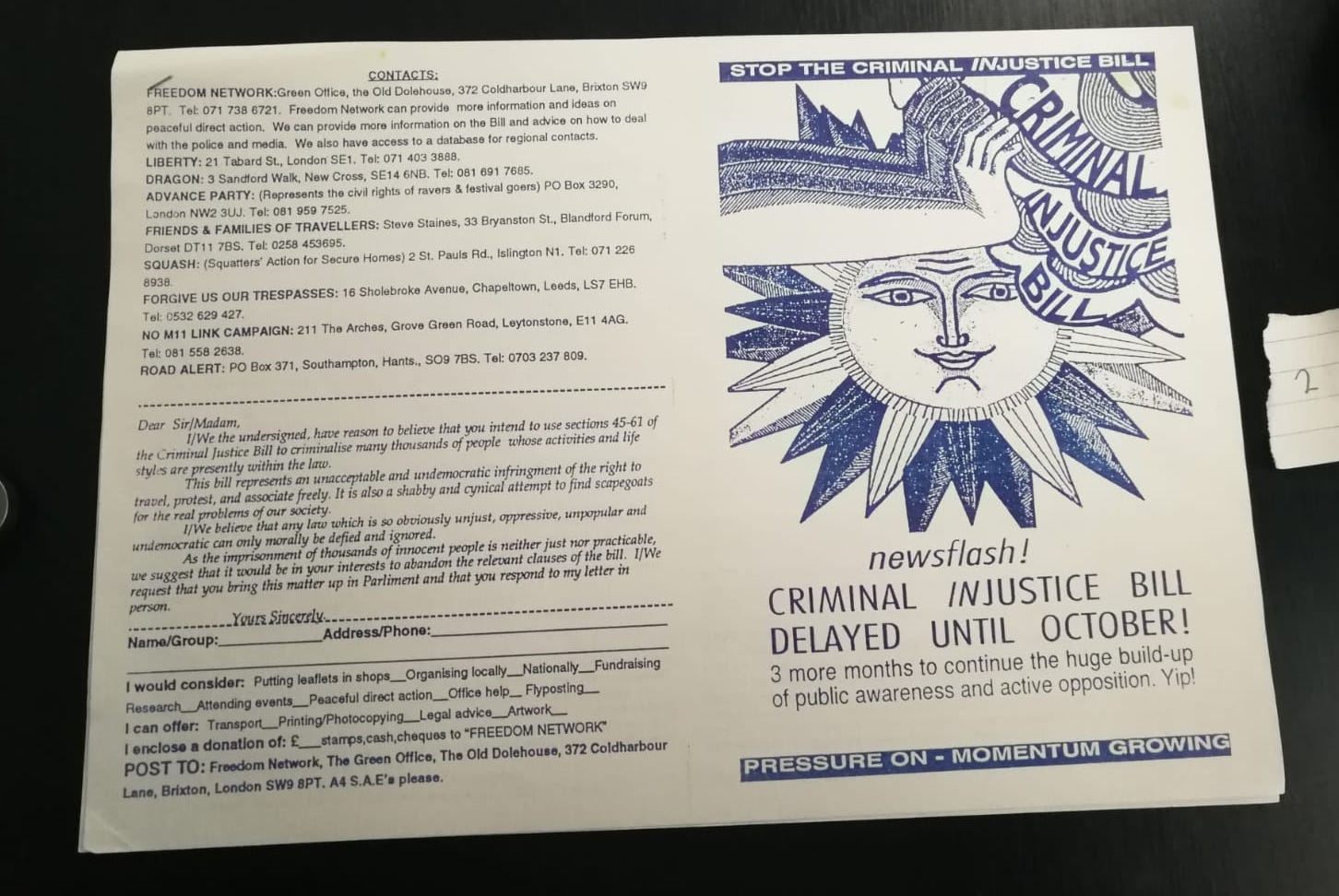

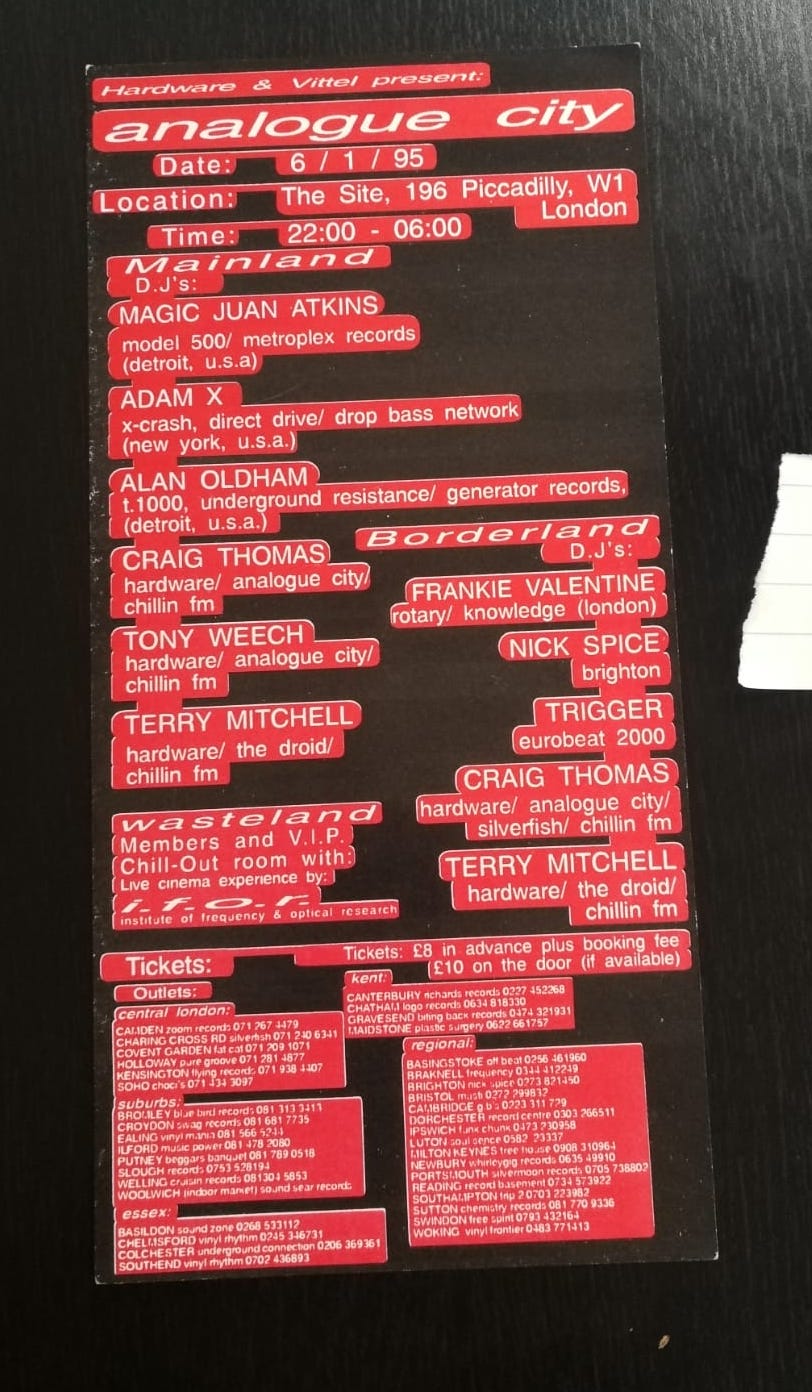

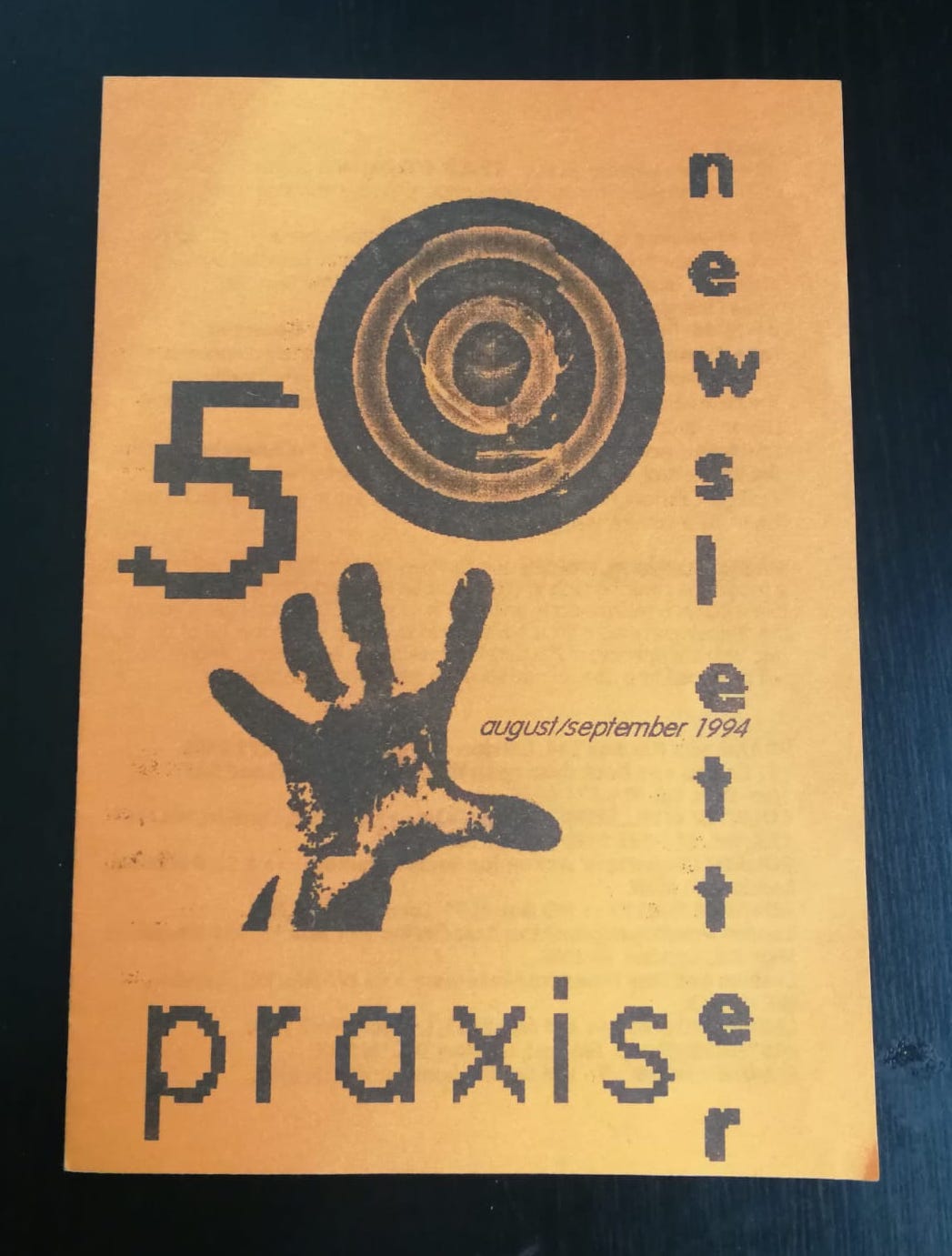

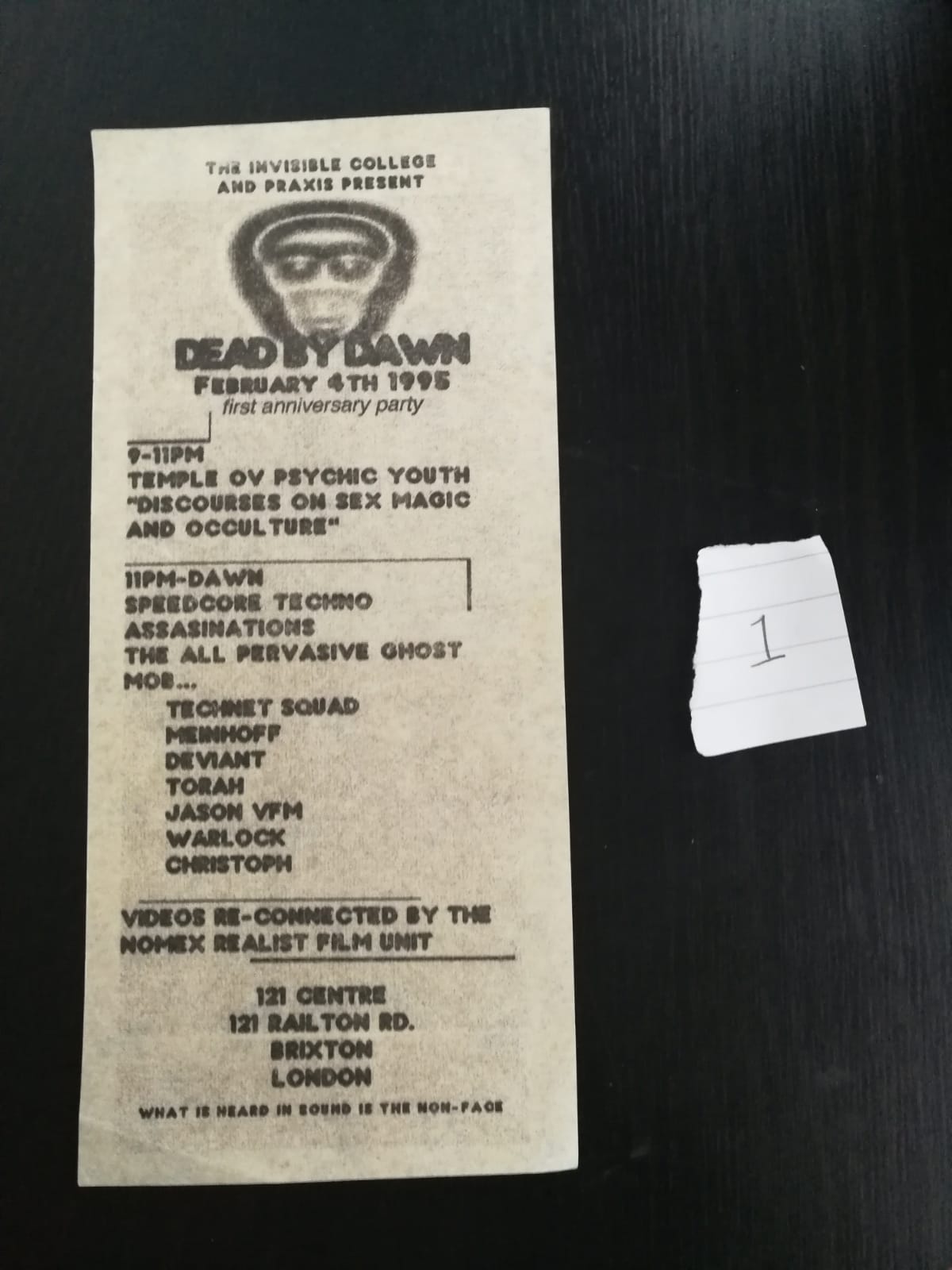

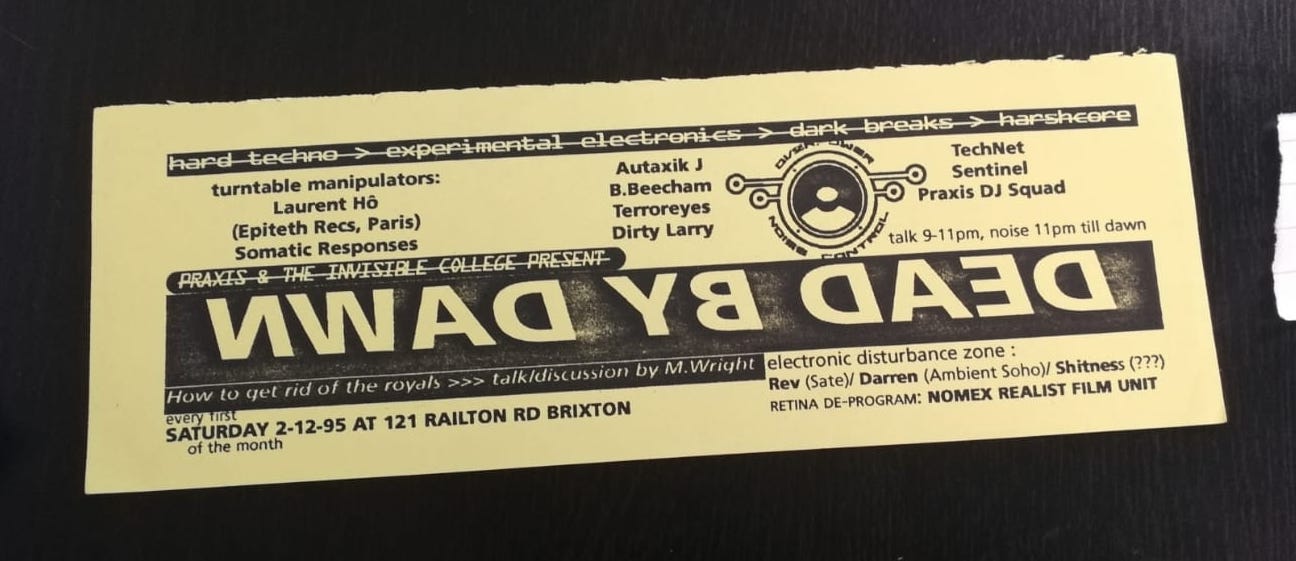

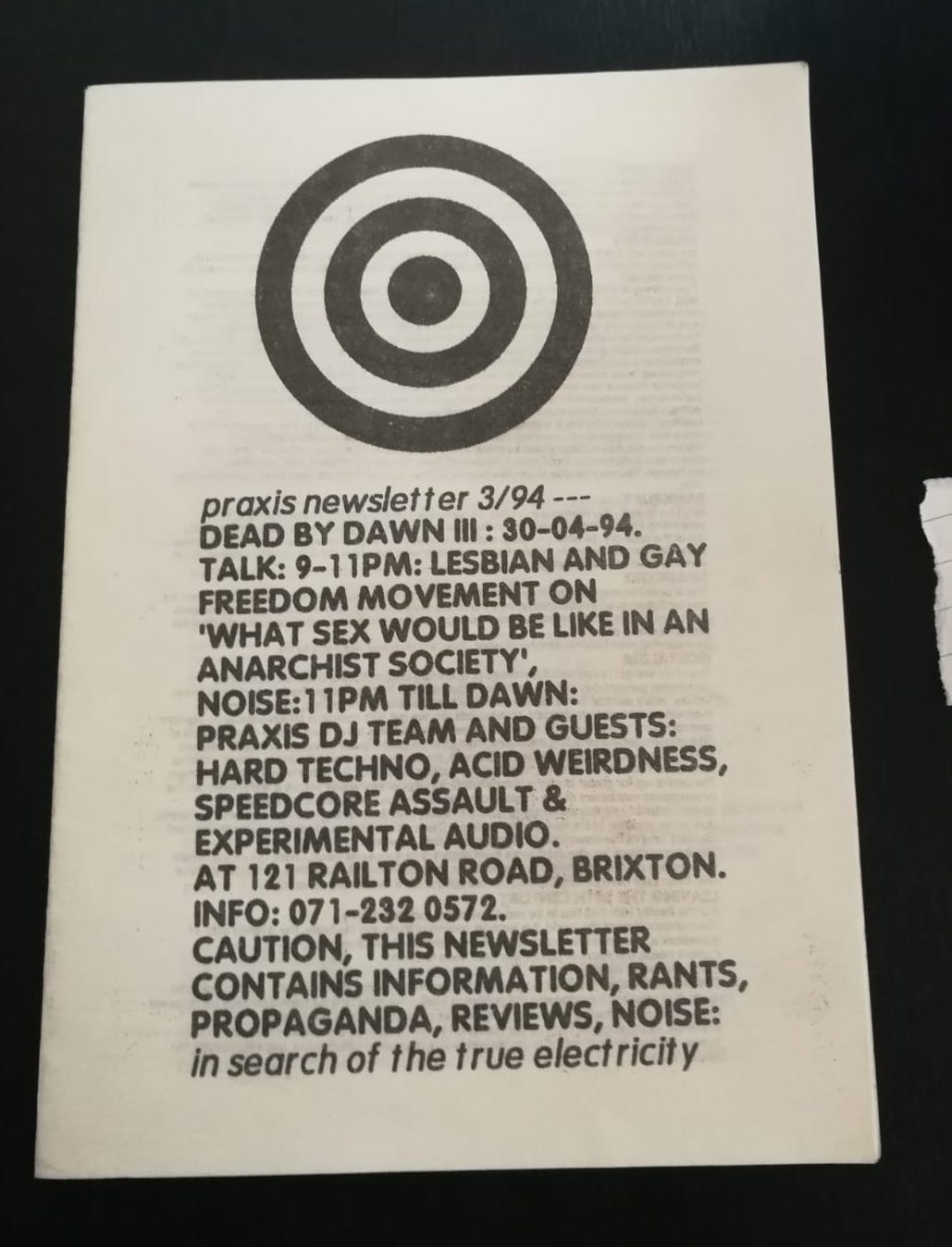

As a mass popular movement that involved and united many subcultures, the rave scene gained political bite after John Major's introduction of the Criminal Justice Act (1993). The ephemera deposited at MayDay focuses on a period from 1993 and the Dead By Dawn/TechNet/Alien Underground assemblage centred on Brixton’s 121 Centre. Amongst the papers are zines from the period, flyers, news cuttings, correspondence and typescripts and drafts of TechNet writings.

Below we present a conversation between between Poppy Tibbetts, Louis Hill and Howard Slater, who deposited the archive at MayDay Rooms. The conversation took place in the afternoon of Friday 31st of January 2020 at Prufrock Cafe in London. The transcript is available below as a downloadable PDF, as an audio file and also in simple text.

Listen here:

Recording starts:

LH: ‘Howard’s brought a map!’

PT: ‘Oh sick…. Oh cool!’

HS: ‘This map is from 2000 actually… When I gave a talk about it. Er, to some friends. Yeah, cos this won’t be in the archive., I don’t think anyway.’

PT: ‘This is like what we were trying to do — [to make a map] from stuff we found in the archive…’

HS: ‘[I suppose] the trouble is it might pre-empt what you’re trying to search for, well if you were trying to map out the connections from the Techno archive in MayDay Rooms, the connections would be London Psychogeographical Society, and Association of Autonomous Astronauts.

LH: ‘Right.’

HS: ‘So when I started doing TechNet , it was called, which was a ‘Flier’…’

LH: ‘Yes, Er…’

HS: ‘…which there might be some in the archive… And this was a re-print of some of them, I did it with a guy called Jason Skeet.’

LH: ‘OK.’

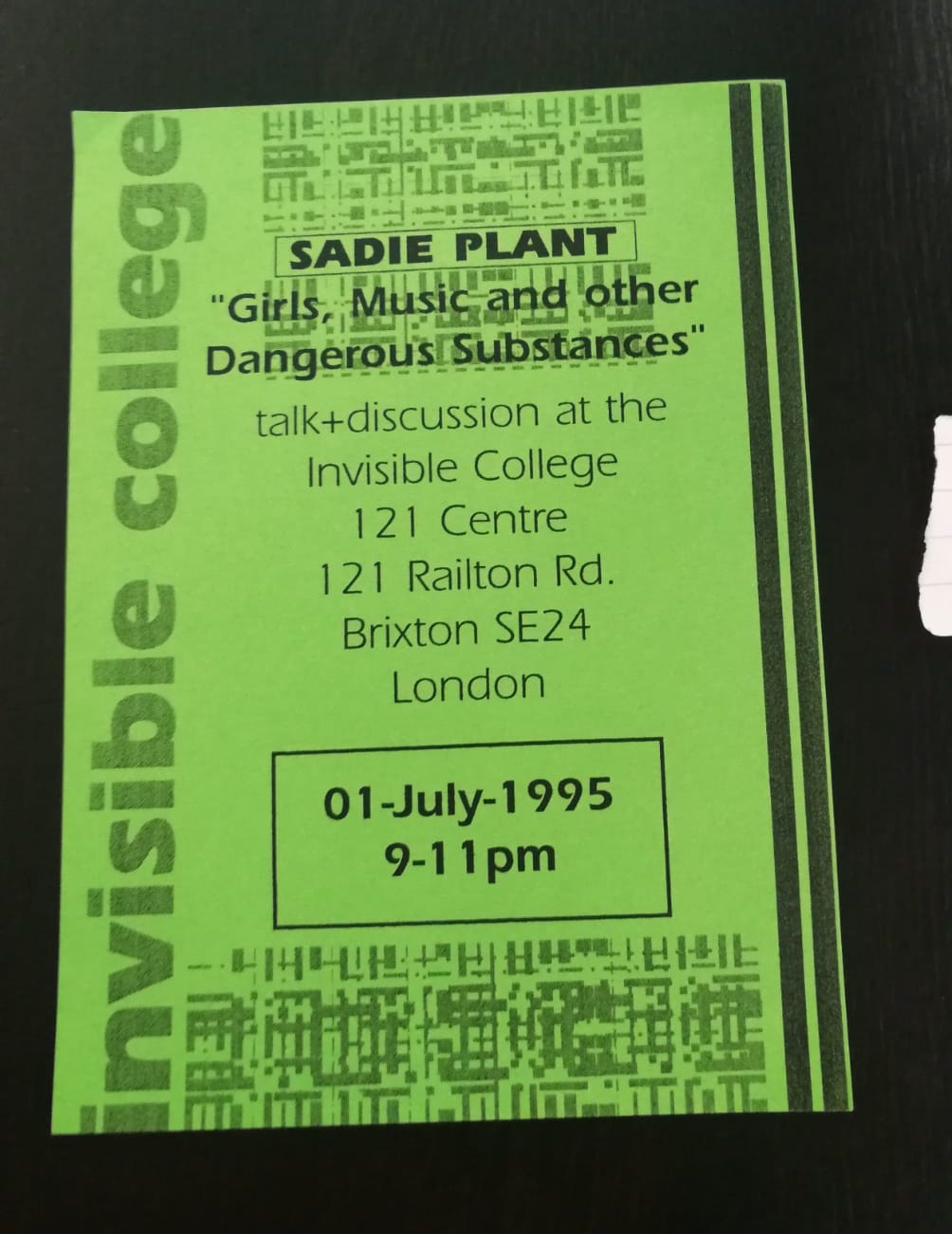

HS: ‘So TechNet itself from about ’93, ’92–3–4—5—6, ’96 , was me’self and Jason Skeet; Jason Skeet went on to become more involved with a Record Label, called Ambush, and; The Association of Autonomous Astronauts. So, Fabian Tompsett of the LPA, he was like, part of, a multiple named thing, like — Luther Blissett… But he revived the London Psychogeographical Association, which was a Situationist, failed Situationist Project, in 1957. So he… and in MayDay there’s maybe a full collection of newsletters that he put out. So ‘The Invisible College’, was kind of like a slogan particularly coming from the LPA and Jason Skeet. So Jason did a mag called Fatuous Times; so it’s all interwoven, it’s pre-internet day obviously, when it was all ‘Samizdat’ and printed stuff — So I still uphold ‘The Invisible College’. I still have a postcard of The Invisible College, and a little calling card Jason made — ‘Now you see Is Now You Don’t. The Invisible College .’

‘So it’s all part of this dynamic of disappearance, or invisibility, clandestinity, auto-didact culture, all these sorts of things; you know? We were never attached to any academic institution, at all, these were all purely, underground, if you would call it that or— endeavours, self-publishing basically.’

PT: ‘Yeah.’

LH: ‘Self-publishing, absolutely. One of the things we picked up on going through the archive was things like calling cards, business cards. So for instance, DJ business cards in one instance. I guess, was kind of new to us in the sense that…’

HS: ‘Right. I’d have to see those because some of those fliers I collected were naffs — naff stuff, just anything to do with the period. Anyway….’

LH: ‘No, I guess one of the things we were picking up on and sort of wanting to explore more was the ‘network-making’ aspect and how that existed; especially if it is outside of an academic context, what the… I guess what the sort of distribution of intellectual information, whether it be by flyering or pamphlets handed out at raves…’

HS: ‘ ‘Newsletters’. ‘

LH: ‘Newsletters. I guess also peoples’ interaction with the music being one that’s not ‘click and purchase’ but much more looking at printed media…’

HS: ‘Well yeah, I mean… Basically let’s say, how do we begin? It would be coming out of already underground, ‘Mail-Art’ -type, ‘distribute your fanzine’ to other people like-minded, which goes back to sort of Industrial Tape Culture…’ show more...

HS: “…And all that sort of stuff — so it was sort of a continuation of that definitely or, moving into that way of operating; for me from a Post-Punk, Punk background as well, with the fanzine thing; so doing your own paper, press and all that sort of stuff was very much…’

LH: ‘It was important.’

HS: ‘Well, it was the only way to do it, because you’d have to spend ages trying to get into a journalist job and by that time you’d got nothing to say about music whatsoever… That’s what the sort of attitude I sort of had, so with TechNet particularly say, it took deliberately the form of a flier, and because we’d go round the Record Shops buying records and seeing all the fliers for all the raves; And back then there were a lot more.

‘So we thought, me and Jason thought, well what we’ll do is we’ll do some reviews of music and sort of… We wanted to politicise the Techno scene, in the sense of, it was a counterculture. At the origins of Techno there’s a lot of snobbery about it; you know like… I was coming out of a [background] of free improv, free Jazz, style of playing, and interest, and I’d hear sort of, Joey Beltram’s ‘Energy Flash’ or this other stuff: Detroit stuff, and think “What the fuck? — some of the sounds I’m trying to get from a bass, are here, in this music”; which is ostensibly a populist dance music, some of which is Hacienda, some of which me Sister was dancing to — Detroit stuff in the North West, you know, or Hacienda. All this sort of stuff, I went completely Head-over-heels for it. I was like, 30, and I thought: “I’m too old for it”.

And I ended up in Fat Cat Records or somewhere like that and I’d find there were all a bunch of other old Post-Punk old guys, 30 year-old guys who were buying this stuff, cos there was a definite linkage to Post-Punk electronic music (Cabaret Voltaire, New Order; early New Order) which the Detroit people were feeding back to us, that was the Kraftwerk and all that… So this is a general history I s’pose.’

[…] ‘The first TechNet was a flier. And the first title of it, that hasn’t been reproduced, was… ‘Networketry’. And er, and then we stumbled upon Noise by Jacques Attali…’

LH: ‘I know it, yeah.’

HS: ‘And we sampled some bits from there, so there’s all the idea of ‘sampling’ stuff as well…’

LH: ‘Sampling culture?’

HS: ‘Sampling text…’

PT: ‘Hmm…’

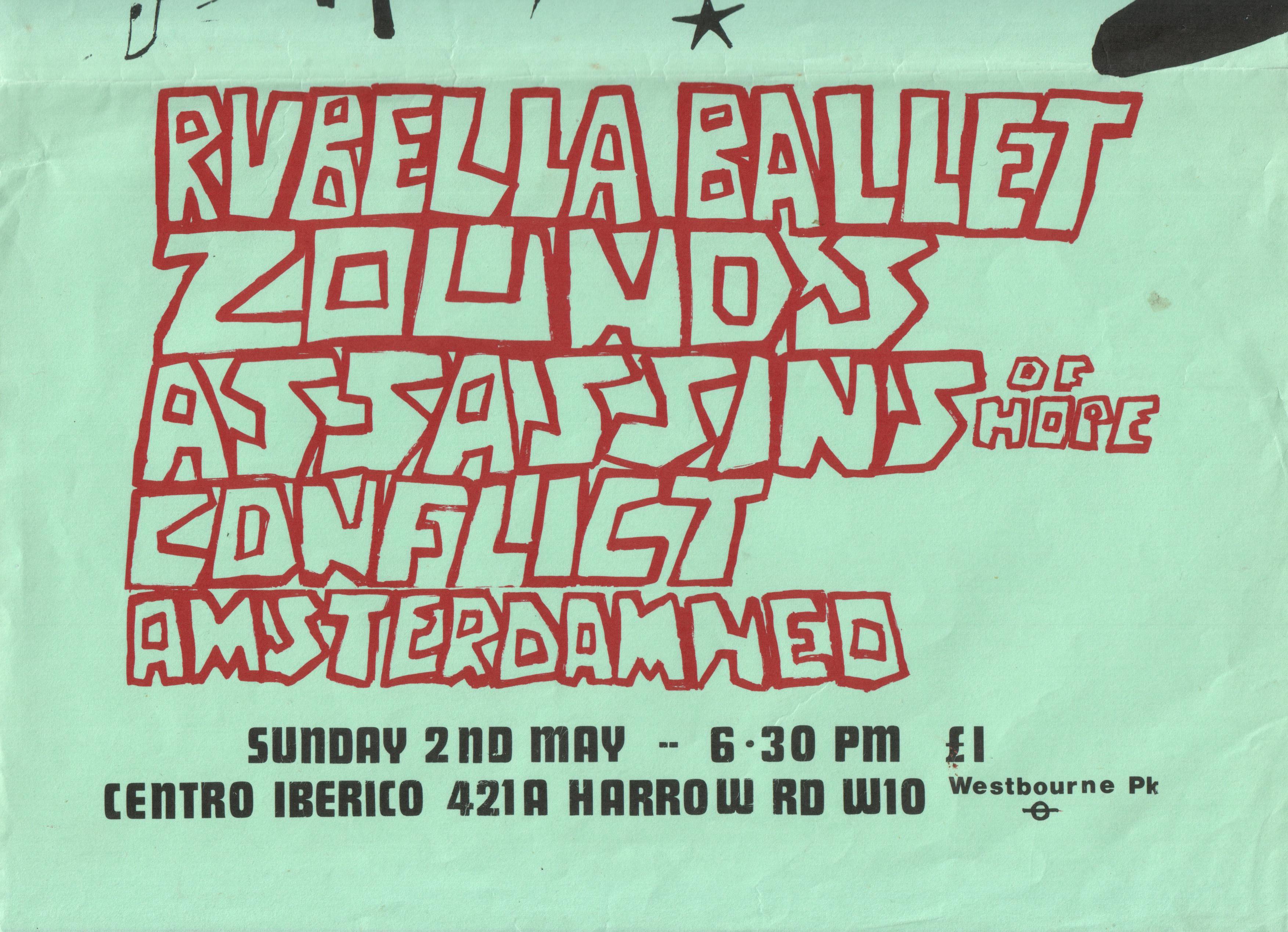

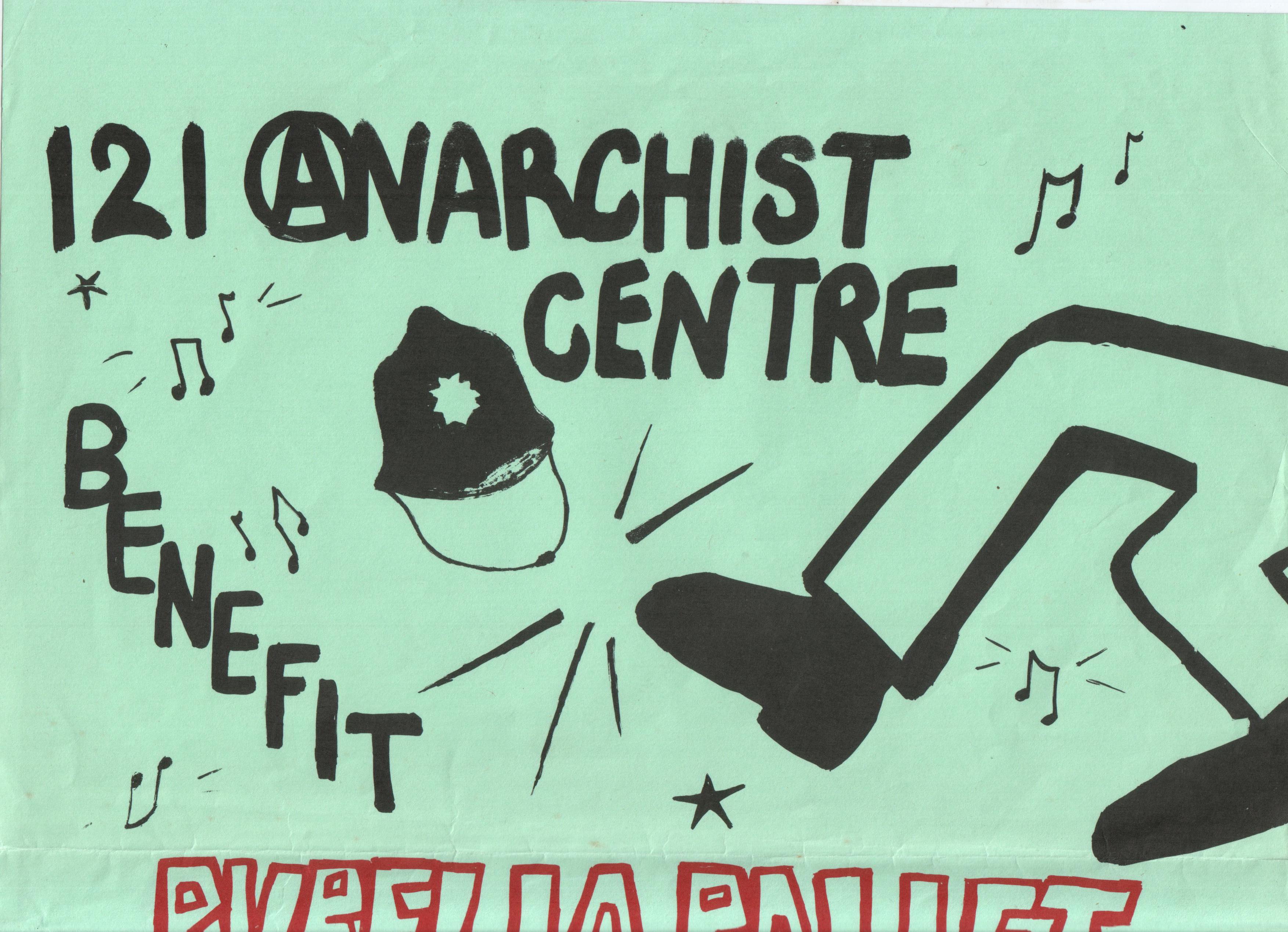

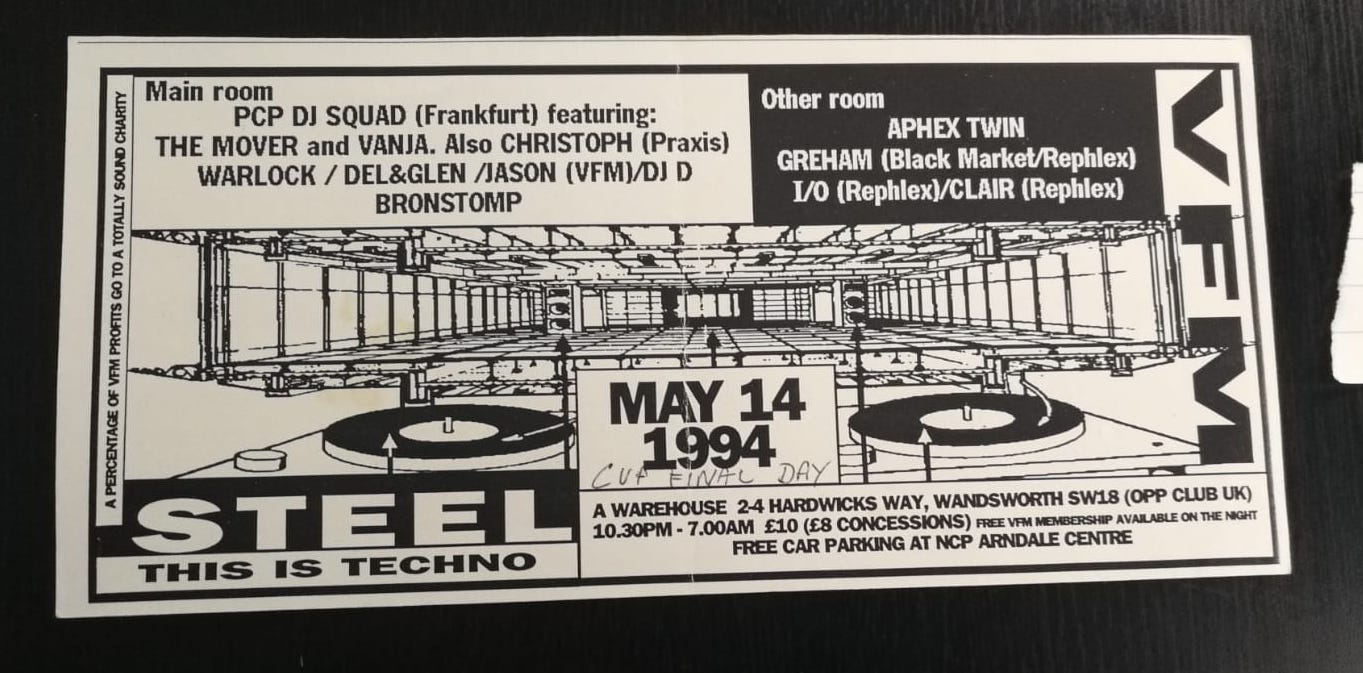

HS: ‘ I mean by the end TechNet’s last thing was a… from the first thing like that the last one was an insert into a double pack album based on the record we made money off-of, with Praxis [Records]. So Praxis, Datacide, TechNet. And we ran a club called ‘Dead by Dawn’, in the anarchist centre at Railton Road. So, that became a sort of hub for like-minded whatevers, you know what I mean? And we’d play about with what we did there. We’d have talks beforehand — Sadie Plant talked, Stewart Holme. Graham Harwood ‘What Would Sex Be Like in an Anarchist Society?’. So it was linked to the fringe-Anarcho, I’d call it…’

LH: ‘Fringe-Anarcho.’

HS: ‘ Fringe-Anarcho culture. At the time that Dead by Dawn started, we were sick to death of agit-prop music being to do with politics. So, at one extreme you’ve got wankers like, ff’—— Billy Bragg, you know like this kind of Social Realist music, so, the Punk-Anarcho scene was like, just still playing Iggy and the Stooges, rock-thrash.’

‘So they even debated whether they would allow a Techno party to take place, in the Anarchist Centre, so that was our —’

LH: ‘Hub?’

HS: ‘Almost… I wouldn’t say ‘Underground’, but there was this anathema to Techno, you know, like ‘Faceless Techno Bollocks’ was one phrase, which people would turn back - with T-Shirts: ‘Faceless Techno Bollocks’, you know like, ‘Repetition’ , ‘cos it was too repetitive. So bands like Unit Moebius would just go till repeat and repeat and repeat. You know, so, there’s all these ways to turn back the criticisms, that ‘was’ Techno at that time…’

LH: ‘With Techno?’

HS: ‘While people who criticised Techno… the acts would turn it back — The people who made the tracks would take it back, the fans would turn it back.’

LH: ‘ So there was an intellectual undercurrent, is what you’re saying?’

HS: ‘Yeah, I think so. I think TechNet was probably seen as the intellectual undercurrent at that time, apart from people in Manchester Poly, Culture Studies department — Someone called Redmond… They did a book called ‘Rave On’, like early ’90’s, but it was a bit tame.

We wanted to infuse it, particularly I would say, with Post-Structuralism: Deleuze and Guattari were absolute, I worshiped them — I still do, if you will. Like, what they wrote on music, well we took slogans from them! ‘What is heard in sound is the non-face’ is a slogan TechNet and others used which was actually pulled from refrain No. 11 in A Thousand Plateaus — it’s in there! — ‘What is heard in sound is the non-face’. There were others. We used the phrase ‘Here Comes Everybody’ which was James Joyce. And the Wake-Up Factory Band had an album called ‘Here Comes Everybody’. So there was a few of these ‘slogans’, going about. So yeah we tried to use, adopt sort of, Post-Structuralist stuff, ‘specially Deleuze and Guattari — To sort of say the music, ‘this music is an intensifier music’, so there’d be a title called Intensifier, you know like: ‘This music is body music, this music is… The mind thinks through sound’ — all this sort of stuff, and that’s been something I’ve followed right the way through to now. Where does the aesthetics of music actually form a politics in itself? You know, rather than it always be separate: I mean I’m reading this book on free Jazz : ‘Black Power of Free Jazz’. It’s not been translated from the French since 1971, and they’re drawing the same distinction — that just because we’ve put a political background on it doesn’t mean to say we’ve neglected, well; they probably do neglect the politics of aesthetics… So for instance, within repetition for instance as a ‘Techno-tactic’, then you could refer to Gilles Deleuze’s book, and say well, “Someone’s written a fuckin’ Four-Hundred-page Philosophical treaty on ‘the power of repetition’ ”.

LH: ‘Mhm, absolutely.’

HS: ‘So, it was all these sorts of things to make the music a counter-culture, to make it politicised in some way, but not obviously in an agit-prop, SWP-type way — like, with you know like early stuff would be ‘No More Words’. So, the critique of language and discourse that comes from Post-Structuralism, we sort of used that. And then we’d find, ‘Ah, Carl Craig has made a track called ‘No More Words’’. So, you find all these networked-links inside the tracks, with this sensibility, that you would bring forward — for instance if you could say, people might say, “Ah well we politicised the music beyond what it was, it was entertainment music”, well I’d refer back to particularly Underground Resistance, and Detroit, particularly Drexciya of Detroit. Probably the finest outfit that scene created for me — there would be the Kraftwerk of the next 20-30 years, Drexciya. But, I found recently an interview with Drexciya and they’re absolutely horrified by the way the Detroit music is being ripped off by white producers, even Richie Hawtin, from Canada and all this… So, you were glad to hear this, you were like “Wow, people are making a stand. They’re adopting the anonymity, the whole political charge of Techno: Well, Underground Resistance was explicit, [I] suppose…’

LH: ‘All I was gonna bring back from the kind of, ‘political aesthetic’ is, I was curious about how, perhaps, distributing pamphlets, whether it be at social centres or at raves, might be a sort of active politics, and, if you’ve got music as components or nodes of, almost nodes of support coming in to reinforce ideas; how much does [the] party culture and community spaces play a part in nurturing a political backdrop to actually appreciating the music?’

HS: ‘Yeah, I think that’d be sort of part of it. I mean, my work began to do a series of things called ‘Halucinating History’, where I would look back to stuff like Joe Meek; ‘Telstar’ ? — and New Order actually, [sic: Video 48, Ed Blah Blah], but the space really that held it together was the Dead by Dawn, 121 Railton Road, every month we had a party. So we’d flier the Record Shops with that, we thought ‘Oh well, TechNet can be a flier: We won’t sell it, we’ll just give it away. It’s just a flier for another party.’ So this whole idea was the text, text itself could be Intensification, as the music could be. Cos we’re not a didactic style, a kind of clip-poetic style, with samplings of other stuff, right up to sampling Heinrich von Kleist in the last TechNet thing: descriptions of ‘horrific sound’ or whatever….’

LH: ‘I know his work. Yeah. Do you want to speak a bit about Record Shops? You mentioned Fat Cat, so that’s Lee Purkis…’

HS: ‘Fat Cat was round here, in Exmouth… There was Chocci’s Chewns — ’

LH: ‘These Records?’

HS: ‘These Records I wouldn’t put on the map of Techno and Rave, but I’d be popping down there — I sort of went into exploring Avant-Garde Electronics, if you know what I mean, so These was the place to go for that, but at this period not so much These, no. Chocci’s Chewns, there was one called Silver Fish, in London. Record shops cropped up everywhere…’

LH: ‘Outside of London?’

HS: ‘Er, Action Records in Preston. Manchester Piccadilly…’

LH: ‘Anywhere in Crawley?’

HS: ‘No not that I know of… Dubstep? That’s South London that…’

LH: ‘Croydon.’

HS: ‘Croydon?’

LH: ‘Only cos, you know there’s - I dunno if you were ever familiar with Irdial Discs?

HS: ‘Yes, vaguely…’

LH: ‘There were a bunch of really famous Techno musicians who had projects on Irdial [footnote: Luke Slater/Morganistic] that [referenced] Crawley, so I was curious maybe that’s just where some of the music came from?

HS: Well, I was gonna mention one in Bethnal Green high road, that turned up above a shoe shop, uh, so there would definitely be one in Crawley, you know what I’m saying, they seemed to crop up, like in the Post-Punk days, little record shops just seemed to be cropping up… and at that time there were a lot more Record shops or hence, there were a lot more places to drop the fliers.’

LH: ‘D’you think that publications themselves concerning Techno music supported the scene, in the sense of activating making music happen?’

HS: ‘I would like to think so, yeah. I mean Jason who did TechNet went to make music, under Ambush Records with DJ Skud. And Praxis. They were very hardcore, records. Very hard, to the point where it wasn’t everybody’s taste. So we’d probably be seen as the most extreme proponent of Techno at that time.’

LH: ‘Is this around 1994, 1995, 1996?’

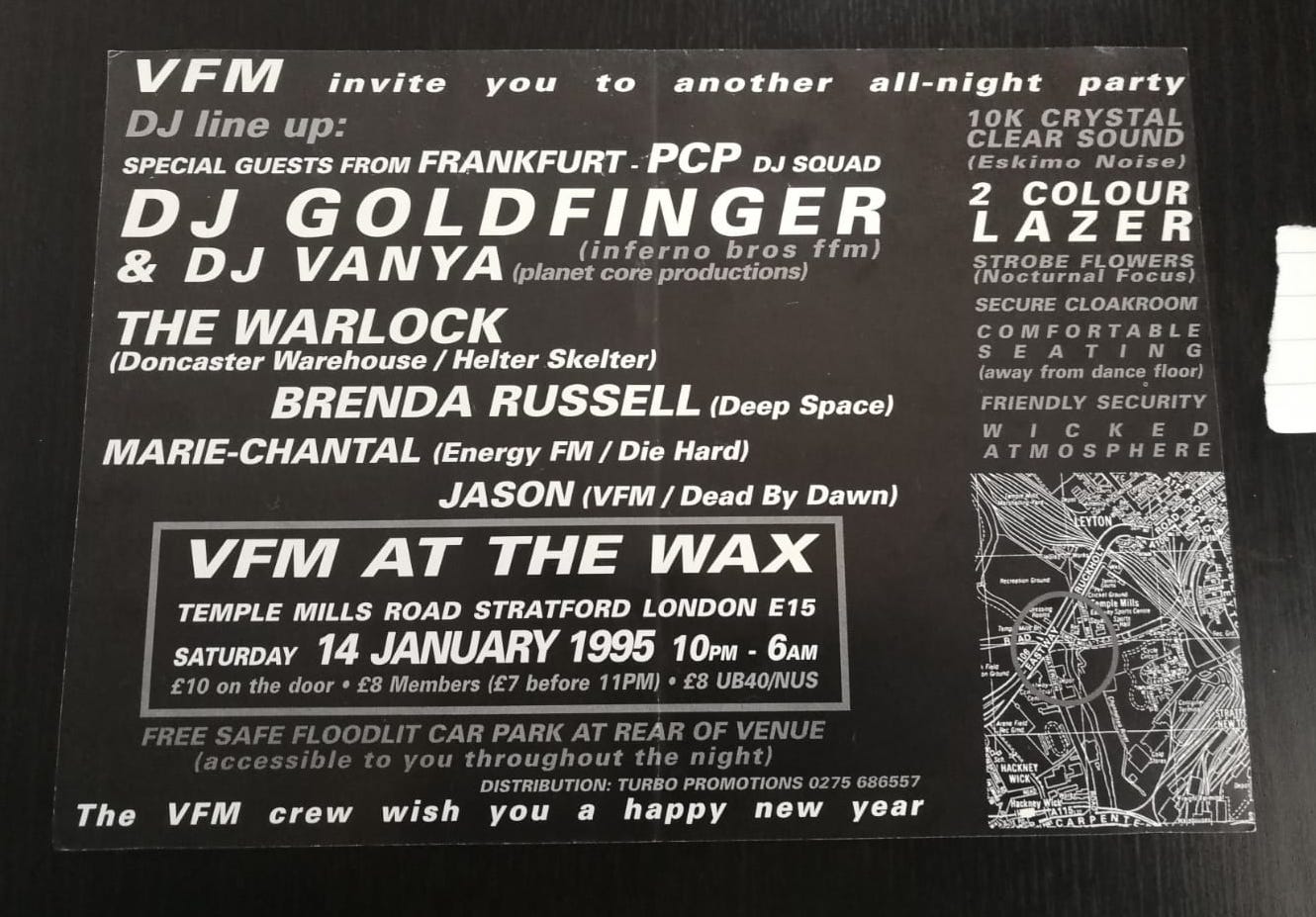

HS: Yeah, ‘3, ‘4, ‘5, ‘6 - PCP Records from Frankfurt, so, Gabber was played at Dead By Dawn, you know, and Gabber — Gabber was obviously, sort of, the ‘shit on the heel’ of Intelligent Techno, you know…’

LH: ‘It’s actively un-intellectual, anti-intellectual…’

PT: ‘It’s really interesting ‘cos like, Gabber seems to be the thing that’s really cool to listen to right now, in squat parties that are happening now in South London…

HS: ‘Well there was, you would say, on a node of this, we had the Criminal Justice Act, and the travellers…’

PT: ‘We really wanted to talk about this actually, yeah. It’s quite a big question but like, what was the effect, was it an immediate effect when that law came into effect, of it kind of clamping down on…

HS: It’s hard to say. We interspersed a sequence from Jacques Attali’s Noise with a reference to the Criminal Justice Act, so textually that had an effect. We knew people like Spiral Tribe, and Spiral Tribe were hounded out of the country, at one point, or still are — and they did a big rave at Castle [Donnington? Morton?].

But also — You’d have to say, the subculture of the travellers… which was also drawing State attention; the ‘Battle of the Beanfield’ etcetera — The travellers were big into Techno, they weren’t sticking with the Anarcho-Punk — the travellers or… Eco-Anarchist? Or whatever they are… They were big into their Techno. So, they were travelling around, putting parties on. So then, the Criminal Justice Act was probably lobbied mainly at first by countryside people, who didn’t want hosts of ‘crusties’ turning up on a field, pumping techno out. So, that was the first time a music had ever been described as ‘outlaw-able’. A sequence of repetitive beats, or etcetera. So the impact it would have, it vaguely brought together various Anarcho’s and Ravers in a series of demonstrations. But, that lobby was never strong enough to stop it going through. We ignored it really, but, we were in a basement at Railton Road, which is known for Blues parties and stuff like that so, no one ever came round…’

PT: ‘…And told you to turn the music down? [Laughs]’

HS: ‘But, attached to Praxis there was various sound-systems , so: [sic?: Hecate] Sound System and others, who would pursue illegal venues and Raves; I went to one in Hackney Wick, about 1997, in a series of disused Warehouses etcetera — that’d be just after the Criminal Justice Act, you just thought, ‘Well, Fuck it— ’ You know what I mean? ‘If they come they come’, but we didn’t even think of that actually — It just didn’t exist, the Criminal Justice Act, in that sense. But, it probably stopped that spread of that culture through the rural areas, and it outlawed certain, well certain sound-systems would go to Europe. I think [Hecate] went, Spiral Tribe went; and they’re just two that I know of…’

PT: ‘They went to Europe?’

HS: ‘They went to Europe. Czechoslovakia first, and then France. France was a big place for a subgenre of Techno called Speed-Core; less heavy than Gabber, same pace but kinda more lo-fi…’

LH: ‘There’s an amazing label called Hangars Liquides — thats got some wonderful ‘Experimental Speed-Core’ [releases] — quite spacious, which is again not the sort of thing you might immediately associate with…’

HS: ‘Yeah well this is it. We were also big proponents of the scene diversifying itself. You know, almost to elude capture, by the media. For instance, I was getting stuff like WARP, ‘Intelligent Techno’ and all this and I thought ‘What the fuck, what’s this? This whole remastering of Techno thing as ‘intelligent’’. Well it was always intelligent — That’s just a record label spin. But, so, and all the thing of selling out, y’know, some of the old Detroit people making naff records… So there’s always still that conflict of selling out, tekkin’ the money. I remember… React Records did what was called ‘True People’, and it was like a box-set, funnily enough there was an interview in ‘Muzik [Magazine]’ which might be in that archive, with some of the people from Detroit who weren’t on it. And rather than like beefin’ ‘Why weren’t I on it?’, they were saying well, React came over and flashed a lot of cash around… And we thought ‘Nah, we’re not gonna take that short term deal’ — and that, ‘True People’, became like, advertised everywhere, in The Guardian, everywhere. So it then becomes a sort of, you know how it works…’

LH: ‘Compilation culture?’

HS: ‘…In the mainstream, ‘This is who Techno is’.’

PT: ‘That represents, what Techno is, or Underground Techno or…’

HS: ‘It’s funny, you see — other people who weren’t on that persist, like Anthony Shakir, Shake Records.

LH: ‘Shake Shakir, yeah.’

HS: ‘Terrence Dixon, you know, these people who weren’t on it, are still pumping out good stuff…’

PT: ‘I think that links quite well to another question we had about — You did say earlier that you would have to have a look at the fliers, and the graphical kind of things that are in there but, in terms of links with corporate branding and all that kind of thing, it seems there’s quite a “tongue-in-cheek” irony in terms of logos on the fliers and stuff…’

LH: ‘— There’s an ‘Analogue City’ Logo that’s repurposed the Vittel logo?’

HS: ‘Yes, I remember that, It’s long… Some Detroit people were playing there.’

LH: ‘So that’s presumably encouraging people to drink water while they’re taking E’s?’

HS: ‘I don’t know… Is it?’

PT: ‘Or an assumption…’

LH: ‘We can only speculate?’

HS: ‘That might well be an assumption; Either a detournement of the Vittel, or… Analogue City were quite a big affair, so maybe they were sponsored by Vittel, and they’re putting a health warning on the flier… I don’t know. But that kind of “tongue-in-cheek” of Corporate… That’s been going for a while that. Throbbing Gristle did it, Factory Records did it, y’know. I’m partial to it, I’d probably find examples in a Record collection or in that weird, deliberately ‘turning-round’ — ‘Detournement’, you know?

PT: ‘I just wanted to bring up this essay that my friend wrote; she wrote a thesis on visual cultures at the RCA. And, it’s about club nights now and corporate branding. And how club nights are… Club nights, spaces, promoters, are having to rely on much more branding by big corporate drinks companies, clothing companies, and how that reliance compromises even the safety of people, anonymity…’

HS: ‘Yeah.’

PT: ‘And then there’s this whole idea of selling out, selling out gives you these ‘things’ , basically money. But what does it compromise?

HS: ‘I think the same thing happens, across any form of music or culture that gets diluted, or wants to make more money. So Dead By Dawn was about making enough money to keep it going, to pay some of the sound-systems that came or acts that came, so we kept a local economy. We had a surplus to make a double-pack record etcetera. So if you want to massify, the big famous one in 90’s was ‘Cream’. I think that became the first superclub. The Hacienda was always a bit of uh… I was always too fond of Factory Records to really criticise The Hacienda… They kind of kept an independent thing going, in a way. But the superclubs started rising, but of course then you get the same record industry tactics and tricks coming in, and effects. For instance: the DJ’s then get mobbed at by Record companies: ‘Play this record! Promote this one!’. So, from the ground up, subjective weirdness gets less, so the more commercial side of the music becomes like a DJ’s playlist on Radio 1. So then the search; I’d go to a rave and wonder ‘What the fuck is this?’. You know I’d have no clue. But the other thing we should mention is Pirate Stations. There were countless of them across the world, across Cities; there were 4 or 5 you could get in Hackney alone. You could walk across an estate and hear different Rave music coming out of different windows — The slightly hardcore Drum ’n Bass thing, the Techno, the this the that….’

‘So, yeah I mean, what really is probably part of the development of Capitalism itself is to create sanitised entertainment. Banality rules, in whatever field it is. Sonic Arts, your field — It’s gonna happen. The banality will be proffered because it won’t kick off what Deleuze and Guattari would call ‘A line of flight’ or an ‘Intensifying Vector’, or open the mind up to a flier and say ‘ugh fucking hell, there’s such a thing as the Criminal Justice Act’…’

PT: I think also something that this essay I was just talking about touches on, I, and what links nicely to what you said about one producer or one group representing the whole of, you know the one that gets to the top represents the whole; Or the one that’s sort of singled out by whoever the people are at the top. She writes about it in this essay… She’s writing more about queer culture and safe spaces, and how people who might be — people from the queer community for instance, are picked say, by Uniqlo to represent the whole of this culture, and also how Capitalism divides us, instead of bringing us together which is like, what, one of the main attractions of club culture? And how, y’know it creates competition.’

HS: ‘Divides and creates exclusivities, things like that? It then creates a fissure in each community because one person’s supposed to be the spokesperson, so they’re the victim sometimes… I’m thinking of Kae Tempest you know, never a big fan of their work, but all of a sudden they turn up on some advert somewhere with that same old delivery style that all spoken-word poets seem to deliver in the same tempo, all the time. And it’s like — There you are. There’s always been this big argument, about this: “It gets to more people, why shy away from the popular?”. But summint about this Techno culture was this anonymity. Was the lack of quality control in a certain way. It seemed to be more important that people were involved in making culture, making music, and dancing to it, or thinking or writing about it, or having it intensifying, than it does for LFO to be No.10 in the charts. I don’t know but, we’re always trapped in this consumer society where this selection process happens, so: Round about this time I started writing these things called ‘Post-Media Operators’, from Felix Guattari’s Post-Media Error. And this was quite a popular text, because it wasn’t so much about a network side of internet culture, it was more about a D.I.Y spirit where we bypass the labels, we bypass journalists — because they become mediators, of a consumer choice variety. All this impact. So there’s a politics of the media, gets brought out as well […] — the very things we’re talking about. What makes a club popular? A certain outfit popular, band-art popular…’

LH: ‘What does the term ‘Cyber Culture’ mean to you?’

HS: ‘To me? [Sighs] God. I’ve never used it in relation to Techno. Cyber Culture would mean to me a genre of science fiction writing at first, William Gibson. And you could kinda graft it on to Techno — probably people do, but…’

LH: ‘Because now, I guess, certain aspects of British culture, culture makers, are being explored with a renewed vigour, people like the CCRU, I don’t know if you were aware of them?’

HS: ‘Oh yeah, yep. Mark Fisher.’

LH: ‘Mark Fisher. Also Nick Land, one of the slightly more controversial individuals.

HS: ‘Oh yeah.’

LH: ‘Also Sadie Plant was involved in the early days.’

HS: ‘Sadie Plant gave a talk at Dead by Dawn. We attended Warwick University — TechNet did. Me-self, Jason Skeet, NoMexx, who’s now dead — he did the visuals, cut up video visuals, at Dead by Dawn. And Cristoph from Praxis. Yeah, uh. How can I put it. They were like ‘Guru people’, Nick Land and Sadie Plant. I was a bit… I dunno. And the CCRU… There’s Kodwo Eshun as well. I was never quite comfortable with that scene.’

LH: ‘You were never quite comfortable with that scene? Their attitudes to Jungle music, for instance, is quite focal in their work. I guess it might have become less so…’

HS: ’Steve Goodman, as well’

LH: ‘But I guess, I’m interested in trying to establish a general sense of what, what ideas around cybercultures and, I guess sort of Network-making at the time might have been. If there were any, and if Techno was associated with that — In a sense, ostensibly early ideas around cybernetics [are] to do with Technology, but it’s also to do with not just a networked grid of information, but [also] human interaction with other humans experiencing something at a certain moment in time — Cybernetic, ideas about cybernetics have changed over time. And, looking at Post-Structuralism as a theme, and thinking about sampling culture in relation to music, in relation to sort of ‘structure-building’, out of what might be…’

HS: ‘Dispersed?’

LH: ‘Yeah, urm… whether the sort of ‘technology’ aspect, that people were listening to at the time, was focal? Or…’

HS: ‘D’you mean, to making the music? It was definitely focal to making the music…’

[Street Market ambience.]

PT: Now we’re gonna get this in the background!

HS: Good sound! It’ll be good… some nice clatter of Techno metallica!’

LH: ‘I guess from the point of view of looking to the input to publishing culture than TechNet sort of asserted at that time… I mean I’m always curious about, how technology influences the production of these things, and obviously nowadays the distribution of information — intellectual information or visual information, is done by different means, so —’

HS: ‘Yeah.’

LH: ‘Actually accomplishing publishing a zine or a pamphlet or a newsletter, would have been done with different methods and in a different spirit than if…’

HS: ‘—I think really, why I can’t really expand — Is this, I would see this period as just before it properly hit, the internet, the web: We were the last gasp of published samizdat, in a way… There was a bulletin board, that me first essay on Techno called ‘Public Energy’ was put on; then there was a thing called NetTime… So they were very few and far between, at the time. Like, these multiple nodes, in the internet world. So really we were looking at correspondence, we were looking at old-school, like, people sending us letters; putting a pound in it, y’know like, ‘send me a TechNet’ …’

LH: ‘ ‘Send stamps to this address’ …’

HS: ‘This sort of scene — I had a list of people who bought TechNet. It was pretty much Cottage, pre—‘

LH: ‘ “Cottage Industries” ?’

HS: Cottage Industries. In that sense, so, the ‘Network’ would always be who-knows-who, comes to play, ‘Oh such and such is in town, they’re coming’ — so it’s a definite friend-of-a-friend’s network; Dead by Dawn was never… Well once or twice we had a shout-out on a Pirate and it was rammed, but usually it was about ‘hundred. You know it was, it was seen as a minority sport, a minority genre, even in the mid-90’s, y’know er, I would say… But the space wasn’t massive. It was an old, dunno how big it would be — wasn’t that big. There was an exhibition of fanzines at one time, during info-exchange, I can’t remember really. Jason did, and Mark [Porsen? sic.] who was a mail-artist — They gathered together a lot of underground press stuff, and they displayed it as an exhibition. So there was an interaction really with the last gasp of printed media — hence the flier aspect, and the importance of fliers in the Record Shops; as a form. We used it as a form in which to write, to disperse, you know…’

LH: ‘And the importance of I guess, I suppose of archiving, erm…’

HS: ‘Yeah?

LH: ‘…for preserving these — To us it’s something that’s very rich because it’s very various, the MayDay Rooms Techno archive…

HS: ‘Yeah.’

LH: ‘And, er… It’s slightly different from someone who’s got a shoebox full of fliers…’

HS: ‘Yeah. I’d been thinking of chucking that out, all of it… Cos I’d moved, and stuff like that. So because I was in MayDay, I kind of almost dumped it in MayDay, if you know what I mean? Cos I had, was a time when all my books were in the basement, I had nowhere to put ‘em all. So it was partly a fact of I had to literally shift, lots of stuff, into MayDay — and then donated it. So, and that stuff was gathered during this period — and it probably includes offcuts of TechNet writing and other stuff like that, and there may be some personal stuff, I don’t know… in there, er, But I probably did have that archival instinct, But I always have: I think ‘One day I’m going to write about such-and-such a thing’. So, I collect stuff, and if I do an essay, whatever it is, I collect loads of shit, and spend like six months before I even write it, you know, er so… It’s partly a process of my own practice, that this came out.’

‘We did have an event, actually, at MayDay Rooms; at the anniversary of the Criminal Justice Act. When Cristoph from Praxis came, and Neil Transpontyne, who does a blogspot called […] well Neil Transpontyne writes for Datacide, and he I think donated a CJA, Criminal Justice Act, box. I think that might be there…’

LH: ‘Quite possibly.’

HS: ‘Yeah, I think that might be there. I’ll have to go back to MayDay and see what’s actually in these boxes. I’m sure we did, cos the idea was at MayDay we’d have an event and encourage people to bring other stuff…’

PT: ‘Yeah.’

HS: ‘…To add to the archive, and things like that. And I’m sure Neil at least gave us copies of stuff he’d collected, about the Criminal Justice Act period. So that was what we would call ‘Activating the Archive’…’

LH: ‘Absolutely—’

HS: ‘You know, so…’

LH: ‘I mean we’ve endeavoured to do the same by opening up the archive to friends and associates of ours, and essentially doing readings from what people have found there that’s particularly interesting to them…’

HS: ‘Right.’

LH: ‘So that forms, some part of the activities for researching this project.’

HS: ‘Well that’s amazing. I could see, imagine — I think that’s amazing. Because I — That was nearly binned. I’d have maybe took one or two choice zines out, and binned the lot of it — but lot, lot of it. You know what I mean…’

LH: ‘So why then, is it important to collect things that don't have a re-sale value, particularly? ‘Cos it’s sort of, I guess…’

HS: ‘I think it’s basically, like a photo album, maybe — It’s like, ‘This was an important period, in my life…’

PT: ‘Yeah.’

HS: ‘In my cultural growing’, and stuff like that, and, you just keep momentos of it, like a photo album. I’ve still got the double-pack, of Dead by Dawn, and I’ve stuffed fliers in it; And me son’s making like, Drum ’n Bass stuff now, and he wants to come and look at this, archive, and I give him the odd flier I find — he says ‘Fuckin’ ‘ell Dad, that’s cool!’, you know like…’

PT: [Laughs]

HS: ‘…Or whatever, so… I think on a, I could take it from the very personal level, to like… ‘I valued that period; even though it’s not got value it’s got value to me’ … Some of it probably would have value in 20/30 years, you know, who knows — but, maybe not… maybe not, probably not. How’d you put it:

‘It’s like the surplus from a project, that — I’ve kept some. Like I’ve said to ya, I’ve been scanning some — I have a filing cabinet and I’ve found stuff in the filing cabinet because someone from the Goldsmiths Sonic Series has asked me to compile some music writings; ‘cos I’ve done more than just the Techno, if you know what I mean. So… so I went back into it, y’know, and I thought ‘Fuck , I better preserve this Fax from Underground Resistance!’, you know what I mean!?’

PT: ‘Mm, yeah…’

LH: ‘Absolutely.’

HS: ‘It’s got Drexciya’s actual signature on it — it’s like, ‘Fuck!’…’

PT: ‘That’s cool…’

HS: ‘So, it’s like… And it means something to me son, so it’s almost like, that level… And in fact, Cristoph is coming over to do a Praxis event at the New River Studios in er, Haringey, on the 21st Feb — so I might be playing something there actually…’

PT: ‘Oh, cool!’

HS: ‘So, and He said ‘What d’you want on the flier?’ I said ‘Let’s call it the “Electronic Disturbance Zone”’ — because that’s what we used to have… Instead of an Ambient room at Dead by Dawn — NoMexx was in charge of the Electronic… So there was always the Rave and the Ambient room, and in the Ambient room sometimes, that fluffy Trance stuff would just go on forever — Peter Namlook and, early Brian Eno… So we thought ‘Right. No. We’ll have, no beats but like, avant garde electronica — you know like, an ‘Electronic Disturbance Zone’.

PT: ‘In a room?’

HS: ‘It was upstairs in the bar area, yeah.’

PT: ‘Ok, so at Dead by Dawn?’

HS: ‘Yeah so, the basement was the Rave, the downstairs was a milling about spot, and the up-stairs was the bar, caff, and the ‘Electronic Disturbance Zone’.’

PT: ‘That’s really cool.’

HS: ‘Yeah.’

PT: ‘Cos I’m much more into Ambient stuff now — I don’t, I actually don’t really like going out that much [laughs] And I think one of the reasons why I asked you that…’

HS: ‘— Well, neither do I anymore! Christ…’

PT: ‘Yeah, I kind of feel like I should, though… Cos, I’m, like, in my mid 20’s…’

HS: ‘I don’t feel like you should ‘owt… yeah. But you can always re-find it back when you’re in your mid-30’s…’

PT: ‘Yeah… I think one of the reasons I asked you that question about Capitalism dividing us in spaces where we’re supposed to be brought together, is like — I think, on a personal level, I’m trying to work out why, I, go to a lot of club nights, like, that are meant to be ‘underground’, blah blah blah, you know like — in a squat or whatever?’

HS: ‘Yeah…’

PT: ‘… And, um, feeling very alienated in those spaces? And that’s obviously something personal to me, there’s obviously a lot of personal…’

HS: ‘What sense does your alienation take — What form does it take? Is it to do with Music? People? Environment?’

PT: ‘I think it’s like, a competitive thing?’

HS: ‘Yeah — Too much competition? Amongst people who should, yeah…’

PT: ‘Yeah, like, ‘Who’s the coolest person here?’ — I know that comes from my own personal resentments… but I think it has something to do with…’

HS: ‘Posers.’

PT: ‘Yeah… And I think this whole thing has been heightened by, like, the acceleration of Capitalism, or something — or the internet, or something… I don’t know.’

HS: ‘Well, I think it has probably been accelerated in the way, culture’s become over the many years, much more of an economic viability…’

PT: ‘Right.’

HS: ’So then, cultural… It used to be called ‘kudos’, you know— the cultural kudos, like, you didn’t actually earn anything, or you didn’t do ‘owt, but you were seen here, or you’d done this in this magazine… So this stuff happens, but I think probably accelerated to the level that, ‘individualism’ gets accelerated, er…I’ve always thought ‘How can Individualism get any more accelerated?’. But I think with sort of, Facebook; Facetime, selfies, taking clips of where you are, and what you’re doing, what you’re eating…

‘So then obviously, Cultural Products come in to show how hip you are, because you’ve found this record from 1962, you know… Maybe these things always…’

PT: ‘So like, ‘Social Capital’ …’

HS: ‘ ‘Social Capital’, ‘Cultural Kudos’ and all that sort of stuff, when… It could come down to a DJ set — What does the DJ drop? — That’s not known… I’ve been involved in that me’self in a way, in terms of like, ‘oh well you know, I’ve got this and I’ll drop this Zimmerman electronic piece, you know and it’ll blow everybody’s mind’, or whatever, but… I think sometimes it’s like; Whether you look to attract somebody through enthusiasm and interest, and mutual desire, or whether you use it to make somebody stand off ya. So I think there can be two ways about it — You want to share something; but if you’re in the business of exclusivity, attached… And if you’re not in a movement, this is the thing — well this is part of a wider movement, like Jazz-men talk about Jazz — it’s like, well, I might be, Lester Bowie, but, I’m actually, Lester Bowie and The Art Ensemble of Chicago, or, the whole South-Side black Chicago Jazz scene, or the ASEM. So, I always find, no matter what — really, that musicians who are more embedded in something, seem to provoke you more in what they do, or there’s some sincerity level there… than just — like, my bug-bear at the time, was Scanner. And he was everywhere, you know like: He was on the NME, he was popping up here, he was popping up there, and er… ugh god, we used to hate him… I think we went to one of his nights at the ICA, and it was like ‘Oh my fuckin’ god …’ It was like what you’re talking about - whatever, let's not bad-mouth people! But, we just, you know… Well he’d scan — I should have liked it really! I liked Musique Concrète, and stuff like that. I love it. But uh, I just found he was, just — anyway. Strike that. But— I don’t give a fuck if he hears anyway! [Laughs] Who am I? He can’t take a lawsuit out can he?’

LH: ‘— Speaking of institutions and I guess less so public institutions, but, er, the importance of certain clubs in the early days of — or rather, the height of Techno [in Britain], were you at Railton Road aware of places like Vox Club, and nights like ‘Quirky’…?’

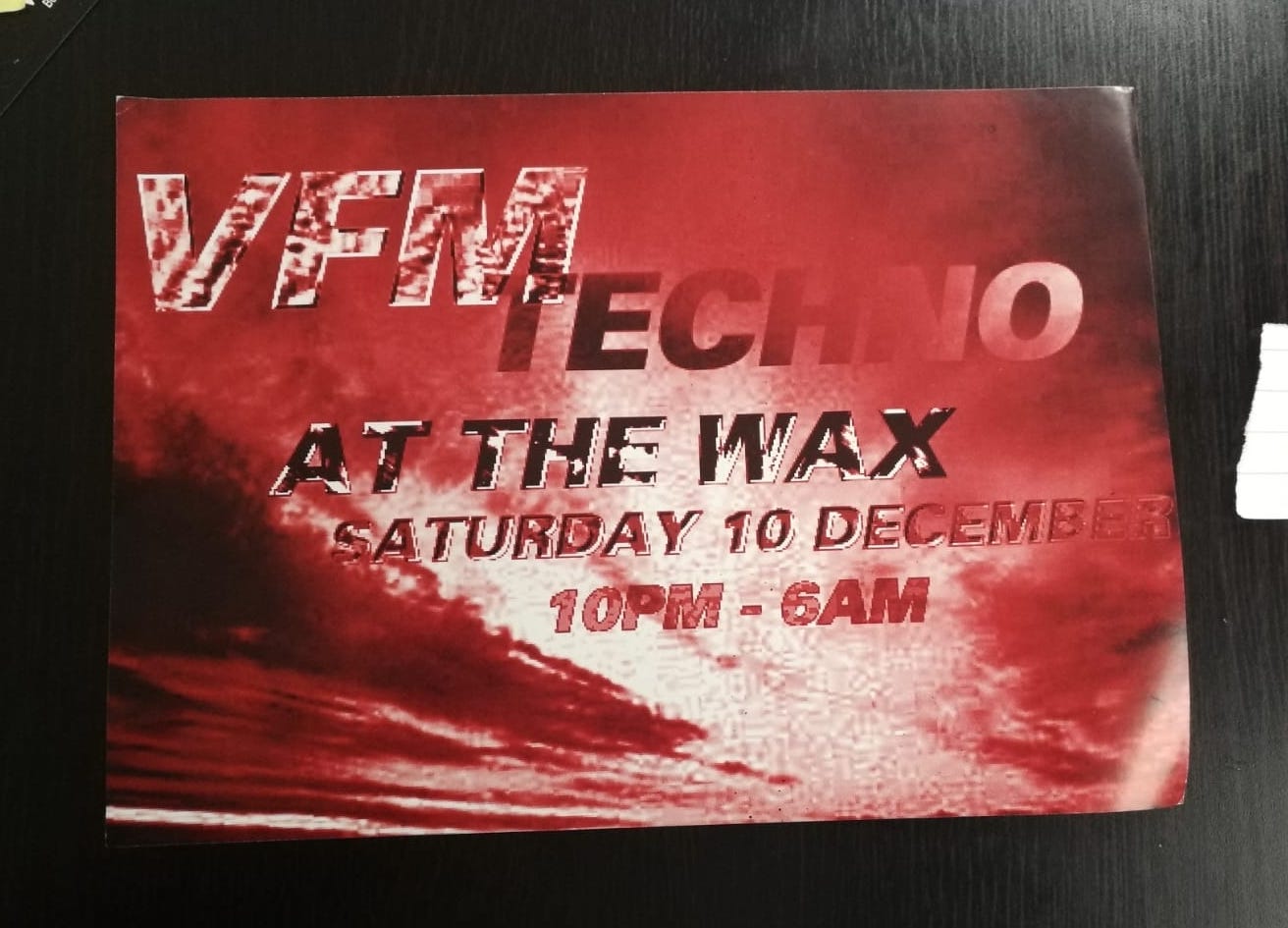

HS: ‘Not so much. No, not so much. I didn’t really go to that many nights… I went to Colin Dale nights like VFM. We used to go to VFM…’

LH: ‘There are some VFM fliers in the archive…’

HS: ‘ Yeah, which is like… bangin’ Frankfurt stuff.’

LH: ‘Okay.’

HS: ‘PCP, The Mover. PCP were a big, important label — they had like 12 sub-labels. They were like, the godfathers; The Mover, who had this sort of — how would you call it — a ‘multiplex sound’ on his Techno. Big, booming bass-drums, it were like bein’ in a multiplex. They had the highest production values, and they were the dirtiest, low-down, coke-snorting, underground pigs really, Frankfur— PCP. You know, they we were…’

LH: ‘ Yeah!’

HS: ‘… Evil Motherfuckers. Hangin’ out with the Croatian football team. It was all a bit, ‘woooah…’. But, they were heavy-duty, so…’

LH: ‘There are some Eurobeat fliers in the archive…’

HS: ‘Yes! I went to Eurobeat 2000 yes, yeah. I saw Carl Craig there…’

LH: ‘And that’s, I guess, I mean that in a sense — picking up on some of the strands of Electronic music from that era — I guess [New Beat] gets quite often overlooked, perhaps because it wasn’t so focal in British culture as a — maybe the morphology of British music sort of took different, harder turnings — but for instance Eurobeat , I guess sort of grew out of … There would have been some influence from — [New Beat’s] something that essentially started out in Belgium right? Those transfers, international modes of communication, through music are quite interesting…’

HS: ‘Well right back from Factory days, when Factory bands used to go and play in lowlands… Dutch outfits would turn up on Factory Records. So Europe became closer and closer — I’d see Techno really as America and Europe in many respects. Like Northern Soul, the records were pressed in Philly, or whatever — the main audience is in Burnley! You know, and I think the ame happened with Detroit, early pressed Detroit Techno. So really it was like : You’d look eventually to see where your home-grown stuff was coming from — Aphex particularly. But Aphex came to us via a Dutch label, R&S. You know so, on that International level, definitely — Techno was, definitely music of abroad, for me. Well, and then you’ve got your LFO’s, was quite fond of…’

LH: ‘WARP Records.’

HS: ‘WARP, yeah…’

LH: ‘I guess that’s when… We were wondering whether, you know, things like the Criminal Justice Act, actually had a more knock-on, Capitalist effect on the music, and whether, you actually have bigger labels picking up on musicians when it’s sort of, more firmly positioned in the mainstream media?’

HS: ‘Might well have done. Yeah I suppose it’s like football, what happened to football in the ’90’s. Post- Italia ’90; The whole game got sanitised, and I think, maybe post- Criminal Justice Act, you don’t have as many — Vagabonds, doing ‘Vagadbondage’; if you know what I mean? So the licensing becomes much stricter, to do a party, so then you’ve got to be more ‘Institutionalised’, as an entertainment industry… All this sort of stuff.

‘And then we get back on to this thing, well, then the labels get at the DJ’s, saying ‘play this, play this’ — so you ‘ave Payola, when the money comes in, whereas — the free parties sometimes would play, people who were part of the parties’ record — ‘cos they used to do that! Spiral Tribe used to put record after record out, record after record — you know like, of just Mark Spirals or someone else. They’d go round to the Hague, which was a very important scene. Unit Moebius…’

LH: ‘— Murder Capital.’

HS: ‘Bunker Records. Bunker, Murder Capital, [I.F], Jan Duivenvoorden, [U.M] — They were big favourites of mine, still. I think them and Drexciya — that whole scene there — they were sarcastic, strictly underground, you know what I mean?’

LH: ‘Mm.’

HS: ‘They used to do almost ‘art videos’, like, found-footage of someone cutting up a Whale on the North-Atlantic… You know like, blubber and [makes hard kick drum sounds] — type sounds… Hardcore.’

PT: And um, I guess like, as well as the CJA, things like ownership of land and property becoming more contentious, and also the law that got passed by — I think it was by the Cameron government — that made squatting residential… I don;t know the ins and outs of that law?’

HS: ‘Yeah you couldn’t squat residential buildings. So it did leave a little opening to squat commercial buildings but — I think you’re absolutely bang-on. I think the property values from the ‘95 til now, are totally — there wasn’t not a spare space anywhere in London almost, it’s like that. Whereas before, people could do raves in Hoxton, places like that. Those empty properties get a value, like you say.’

PT: ‘…And if there are empty properties, there are either security there full time, or, property guardians, of which I’ve been one!’

HS: ‘ Yeah, I’ve been tempted too! It’s a cheap way to live in London or whatever…’

PT: ‘But I’ve got friends who are against that as well, y’know — I’ve got a friend who does still squat, and she’s very, like, ‘I would never do that… y’know I’d never be a…’ — And I was like, ‘Well I’m paying £300 a month to live somewhere!’, so… But yeah, I feel neither this or that about it… But yeah, property guardians, it’s pretty exploitative…’

HS: ‘It’s probably like, you know — this whole scene, ‘ere, was related to a squatted Anarchist centre, that had managed to be there for years and years — I think Black Power meetings used to happen there, in the ’70’s. It’s been long-known, em, but then it moved in, got evicted — and now it’s probably a Hotel!’

PT: ‘We actually looked on Street View — It looks like it’s new-build flats! Um, yeah, so what actually happened with 121 Railton Road — When did it start and how did it end?’

HS: ‘That would be a different story, that I wouldn’t know — I know there’s definitely Chris [Jone], of 56a Infoshop, I don’t really know him…’

LH: ‘—It still exists, I used to live down the road from there.’

HS: ‘ Chris would be — probably have an archive in there about it. 56a is amazing… And the other guy is Neil Transpontyne — See in MayDay whether he’s left a CJA archive — and he’s good on Criminal Justice Act. I’m tryna get his blogspot, ‘Dance by Night’, or something like that — If you put it in it’ll come out — Neil Transpontyne.’

PT: ‘Okay.

‘And were you involved in … We found a really great publication in the Criminal Justice Act folder, about… It was basically about battles that have happened with the Police…’

HS: ‘Hyde Park?’

PT: ‘…In London — Yeah and there was a long account of…’

HS: ‘Neil put that one out, yeah — I think that’s one of Neil’s, yeah, definitely think it is.’

PT: ‘It’s really good. Did you go to that? Were you involved in any of the protests that happened?’

HS: ‘No, I went on the CJ demonstration that went round Trafalgar Square.’

PT: ‘Okay… Is there anything else you want to…?’

LH: ‘We’ve got… One sort of slightly divergent question, which is about er, current-day exploration of underground culture… I mean, do you explore ‘underground culture’ in the same spirit that you did in the ’90’s?’

HS: ‘I hope so, yeah. But my interests are totally divergent — I’ve studied, like, anti-psychiatry movement… Er, and I think, in relation to this, area — music… I’ve rediscovered it — with YouTube, you can find the old stuff but find new stuff, so… I’m still interested in what’s going on in, like, hard dance-music, type thing — an’ me son’s interests, I swap tracks with him. So… So for instance, a label that I quite like these days is L.I.E.S [spells abbreviation] … I kind of like that, er, dirty, sort of lo-fi house…’

LH: ‘Tape-Techno?’

HS: ‘Yeah, is that what it’s called?’

LH: ‘Well, I guess… I guess they came out of the New York Punk and Noise scene, so yeah, so…’

HS: ‘Right okay… It sounds as though it’s got a similar spirit to Bunker, some it’s a bit grungy, er, and it’s got that Funky House thing… I was always a bit against — Gabber was always a bit too full-on for me. So I kinda like that funk inside it. And the ‘dirty timbre’ was a phrase we coined. That we were looking out for this dirty timbre. This grit — grit in the system. So that sort of L.I.E.S… I like Galcher Lustwerk.’

LH: ‘Yeah.’

HS: ‘Uh, and then… Yeah just various bits and bats. Mainly through YouTube— the last 12”’s I bought were probably Dubstep… That was the last period. Darqwan — Oris Jay…’

LH: ‘Yeah, Oris Jay’s great!’

HS: ‘… That’s the last record I probably bought, but now, I don’t even buy CD’s!’

LH: ‘What d’you think about music journalism nowadays? I mean you said a bit about…’

HS: ‘I don’t read it.’

LH: ‘You don’t read it.’

PT: [Laughs]

HS: ‘I don’t read it — No. I used to… WIRE, y’know, but I don’t read it. If anything, I’m sick to fucking death of English, er how d’you put it — I dunno. Oh, but it’s Brexit day, innit!’

PT, LH, HS: [Mutual Despair]

HS: ‘…But I have this real prejudice against, sort of, ‘Englishness’. I dunno what it is. Like, ‘English People’, phweuhrr… Like Rob Young writing a book on English Folk Music, it’s like they’re all touting this, it’s like the Billy Bragg factor! At least Techno we went to Europe! You know what I mean. I hate this way that the industry, Nationalised Industries, create money to dig and dig in British, in English cultures… To find what? Delia Derbyshire? Not bad. But you know what I mean?

‘I mean I’m maybe speaking a bit out of turn there, but I do have this, horror of, middle-brow English culture…’

LH: ‘The English idiom…’

HS: ‘English idiom, yeah. I try to read books in French now… Yeah, that’s a horror for me, I dunno what it is, I have this instinct against it — I hate it [laughs].

PT: ‘That’s interesting…’

LH: ‘—Fair enough.’

HS: ‘Yeah I’ve got not interest in… No, I guess my — I like to dig for the obscure, un-forgotten. And find them pearls, inside it. So for instance, with French writing, I’m looking for the stuff that’s never been translated into English that’s bang-on. You know, to me, anyway. It’s hard to encapsulate, 30 years of research, in a couple of sentences, but…

‘The last thing I did on music was for Caesura Magazine; There was a pamphlet called ‘A Blind Eye Turned: Music and Libidinal Economy’ — It was supposed to be about Luc Ferrari, which I’d written about before, in 2000-and-summet, and I ended up going through, like, the Industrial stuff, er- 23 Skidoo, Nocturnal Emissions, and like, into Luc Ferrari… I’ve got a scan of it, I could send it ya…’

LH: ‘Yes please.’

PT: ‘Is there anything else we wanted to ask? Some questions on my phone… We did want to ask about ‘optimism’ — so you still want to ask that question? You phrased it better than me, in how it relates to the music… and also the Millennium being on the horizon, ‘blah blah blah’…’

LH: ‘Yeah, absolutely — We were curious about…’

HS: ‘— Which Millennium? Oh, at that time? Yeah, well yeah maybe it did give this speed-up, intensity factor — the BPM grew up, things got a little bit… and then it just piddled out…’

LH: ‘—It’s in, to my ears anyway, lots of the chord progressions — that you can hear across British Techno but then also early Jungle music — sort of. ‘Timeless’ by Goldie. Some of the pianos in Omni-Trio — I’m borrowing a little bit from Kodwo Eshun here — urm…’

HS: ‘The refrain? It’s a three-note thing [dernk-nernk nernk-nernk nernk-nernk] Cubic.’

LH: ‘Well also sometimes, y’know — I think nowadays with electronic musicians who, a lot of the time, aren’t musically trained, they’re learning how to make melodies to do with how they feel…’

HS: ‘Yeah…’

LH: ‘And a lot of the time you get a sort of irresolution, in electronic music, that can work to the advantage of, kind of ‘accelerationist’ ideas or ideas about ‘repetition’ — there’s a sort of… The ’90’s is fascinating to me, partly because there's a wonderfully strange ‘irresolution’ in a lot of the melodic musical aspects, that almost feels, a bit like a time capsule…’

HS: ‘The word I’d use would be ‘Suspension’ — like you’re feeling suspended. I think I can get that in many musics — Jazz… Any music, maybe not just that ’90’s music, but this ‘irresolution’, this heterogeneous thing that’s moving somewhere but not quite sure where it is, or ‘when’s it going to tie up at the end?’ — But I’ve always loved things that don’t tie up. So the narrative idea, of mainstream narrative, is another anathema to me — like, why should anything tie up? But maybe it’s that hovering sense? Like I think, for me, Techno’s use of synths, makes that sort of, hovering, ‘suspension’ thing, on which this other stuff is going around; I don’t know how to describe it, musically but…’

PT: ‘Do you think that relates to the space you might be in? Like the club space as this kind of ‘Utopia’, kind of autonomous space where you can be in that kind of space emotionally, I dunno…’

HS: ‘Yeah I think there’s definitely something to do with… because there is an emotional strain in this dance music, like the synths, the unresolved melody… It’s more like an ‘affect’, than any noticeable emotion, or feeling — which is very interesting for what you say — If people aren’t trained then they’re trying to write what they feel — which is to me, is like saying ‘well they’re using affect, to communicate to us, not necessarily : [sings melody] … You know what I mean? And I think that aspect, was definitely… Instrumental music as well, I found like; If you don’t have the guiding voice, you’re free to float about in it. With the club, the smaller it is — you do get that sense you are together. Even big places I’ve been — you are together. Maybe everyone’s on ‘E’, I don’t know but — I never took drugs to listen to the music you know, but — Yeah, and I think that ties up with that question ‘Do you feel optimistic’… I’d say every time I listen to music I feel optimistic; more or less, that’s a bit extreme!

‘But no matter what it is, it does it: That’s it. If there’s people making music, and there’s this whole history of brilliant, brilliant music, of all genres — well ‘cept Country and Western…’

[Laughs]

HS: ‘…You know, there’s room to all! Really. It’s got the power, I believe it’s a political force completely — without having to even say ‘I am politics’ or anything like that… To me the future of politics lies there; how we understand politics…’

LH: ‘The future of politics lies…’

HS: ‘The future of politics lies in music. Like Jazz - I did a lot of studying of Jazz, and Free Jazz, and like, the way people play in Free Jazz versus ideas that people say: ‘Ah, it’s just people wanking off!’ — No, I’ve spoke to Jazz musicians, I’ve tried to play it a bit — You can’t wank off without something else in the milieu! Know what I mean, there’s a whole complexity of individual mass: the collective and the soloist, the soloist and the collective — it’s very much more complex than just, ‘someone’s wanking off’… Y’know so, to me studying the way Jazz, or Improv, works, is a political progress to me… Is a progressive thing, cos so many political groups break up, y’know… MayDay to me ended up in, egotistical rubbish, or whatever… So, somehow, what can keep people together, in a position where they can become more than what they are — progress, develop. And I think sometimes institutions hold that back; So we need to work the surplus, of what it is between all of us that generates something else — like Burroughs ‘The Third Mind’ — the space between… all this sort of stuff. And I think music operates it extremely well… Y’know, if it’s a bit of detritus from a synth, it’s this bit that’s left behind — ‘What’s that doing on the track?’ — the bits of uselessness. ’

PT: ‘Hmmm…’

HS: ‘Yeah so that’s the life’s work really… [laughs] — not my own either!’

LH: ‘Fantastic.’

PT: ‘Thank you so much.’

HS: ‘That’s alright. I’ve been away…In a trance. Chain-smoking.’

PT: ‘No it’s great. I can’t wait to listen back to it.’

~

Image notes: All the ‘scans’ on this page (anything that is not a phone picture) are from the 56a Infoshop Railton Road archives, the rest are from the MayDay Rooms archives or Howard Slater’s personal archive.