Radio Future Past

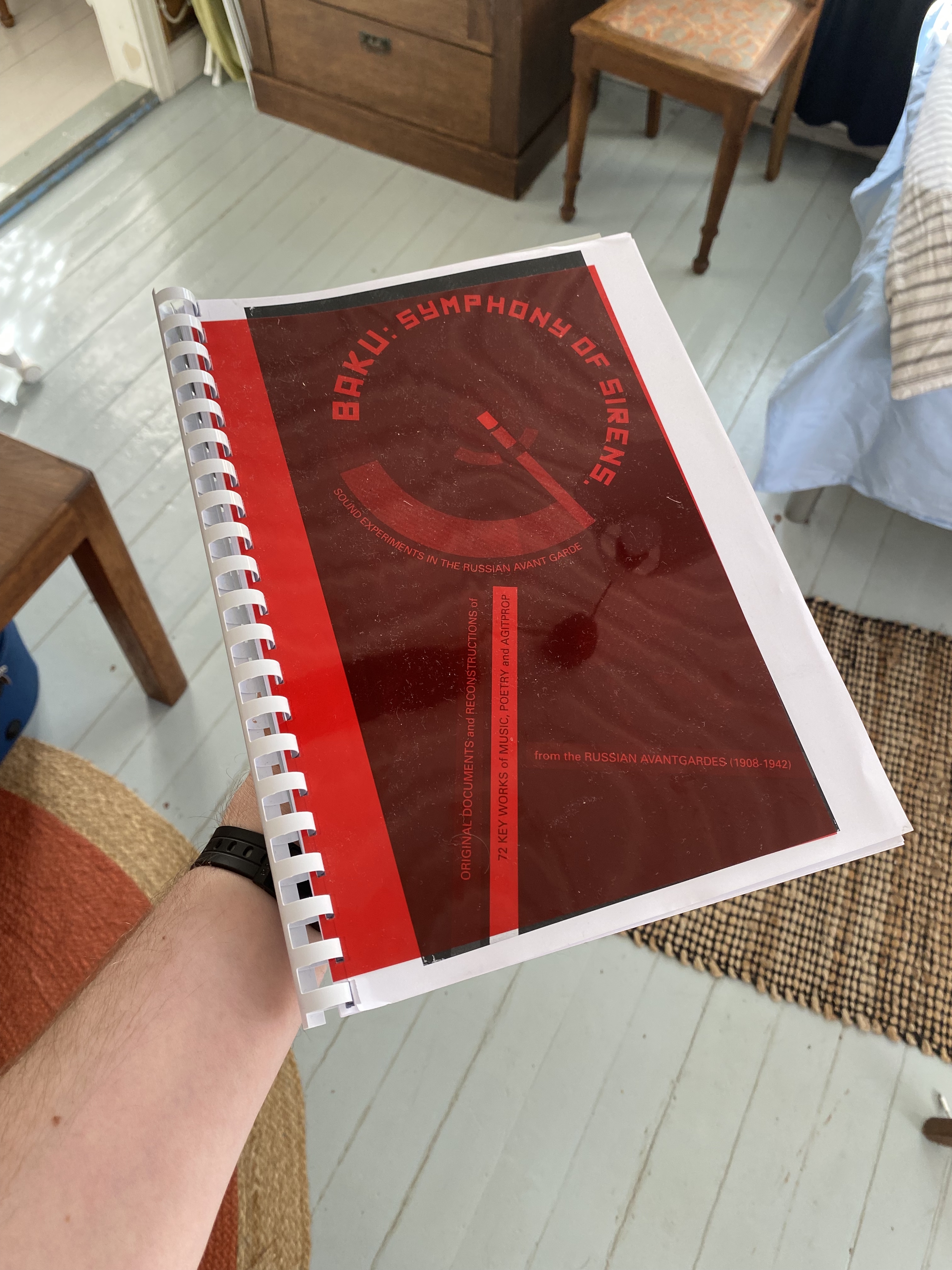

As part of a residency at the Kuvataideakatemia / Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki in May 2025, Sam Dolbear wanted to work through a 2008 book about early avant-garde radio techniques in the Soviet Union written by Miguel Molina Alarcón and translated into English by Deirdre MacCloskey. For the first period, Sam will listen to a radio work once a day and make notes on it from the book.

Wednesday – 7 May

Velimir Khlebnikov, The Radio of the Future, 1921

You can hear singing, wind, bells, bird song, planes, a spring quartet.

From Miguel Monila Alarcón's book: "Khlebnikov was a writer, artist and poet, also interested in mathematics, history, mythology and ornithology (he wrote an article about the cuckoo), A key artist in Russian cubo-futurism, he was constantly searching by way of verbal experimentation, writing toward the utopia of a "stellar" universal language. "The Radio of the Future" is an essay written at the end of his life anticipating the possibilities of the new radiophonic medium (radio first started broadcasting in Russia in 1922). He conceives radio as a "central tree consciousness" or "a great wizard and sorcerer" which, with its waves, would "unite all mankind". He saw the radio station as "a spider's web of lines" or "the flight of birds in springtime" which reveal the "news from the life of the spirit". In the hands of artists, this new medium would transport and project ideas instantly to the "unknown shores" of all humanity. Khlebnikov imagined that they could make "Radio-Books", "Radio Reading-Walls", "Radio-auditoriums" (" a concert stretching from Vladivostock to the Baltic"), "Radio and Art Exhibits", "Radio Screens" and "Radio Clubs" ... where you could see and hear everything from the tiniest sound of nature to major events in the "exciting life" of cities. He understood that with this there would be a communication between the artist's "soul" and the people: "the artist has cast a spell over his land; he has given his country the singing of the sea and the whistling of the wind. The poorest house in the smallest town is filled with divine whistlings and all the sweet delights of sound." This capacity of Radio led him to see it as "The Great Sorcerer" capable of transmitting even "the sense of taste"; people would drink water feeling that they were drinking wine; or smell: a Radio station "would give" the nation, for example, "the odour of snow" in the middle of spring. It would also be a "Doctor without medicine" curing from a distance by means of "hypnotic suggestion". And Radio could also transmit sounds to facilitate the work of the harvest and construction by emitting certain musical notes, "la" and "ti", which would help "increase muscular capacity" in the workers. Another of the Radio's great qualities would be the organization of popular education through radiophonic classes and lectures."

Thursday – 8 May

Ivan Ignatyev & Ego-Futurists Group, The First Spring Concert of Universal Futurism, 1912

You can hear voices, bells, pipes, winds.

From Miguel Monila Alarcón's book: "The Ego-Futurists organized "banquets & soirées", combining sophisticated products (such as "Crème-de-Violettes" liqueur) with refined poetry recitals ("poesas"). It was their way of protesting against the intolerant petit-bourgeois public who rejected the excesses of the Italian Futurists, while getting excited listening to the works of Rimsky-Korsakov, Tchaikovsky or Saint-Saens. For May 1912, through the Petersburg Herald, they programmed a "poeso-concert" announced as "The First Spring Concert of Universal Futurism" which was to be performed at midnight in the suburbs of St Petersburg in the park next to Paul the First's Hunting Palace. This event included, alongside the recital of poems, "Pavilions of Seclusion, of Ego-books, of Milk and Black Bread", a "Chalet of Cupid" and an exquisite buffet of "Wines from the Gardens of Prince Yusupov", "Crème-de-Violettes" liqueur, "Gatachino Pink Trout", "Fleur d'Orange Tea" ... The park was to be decorated with "lilac illumination" and there were to be "aeolian bells, invisible ocarinas and pipes" (partly included in this recording). It was from these elements that this recording was made since these were the effects that would supposedly have been heard had the event taken place - because in the end the "poeso-concert" was cancelled due to the bad weather in May 1912, and because of disagreements with the management of the Petersburg Herald who finally decided to replace the event with a publication instead. The event was organized by the ego-futurist Ivan Vasilyevich Ignatyev (1892-1914) and was to include Igor Severyanin, I.V. Ignatyev himself, Constantine Olimpoz, and I. S. Lukash. After the exclusion of Severyanin, Ignatyev - the new leader of the ego-futurists - had created an "Intuitive Association" in whose "Charter" he claimed: "God is nature. Nature is Hypothesis. The Egoist is an Intuitive. An Intuitive is a Medium". Thus we understand why this futurist concert was organized for the start of spring: Ignatyev said that the Russian bisyllabic word "Vesna" (Spring) contained the essential and spatial meaning of the arrival of spring, with the phonetic of the letter "s" ("an impression of sunniness") and the "a" ("joy of attaining the long awaited"). With such examples Ignatyev defended various senses in poetry: colour, sound, taste, touch, weight and spatiality, thus "poeso-concert" evenings with food, drink, sounds, colour and poems were another way of carrying forward a "Universal Futurism" experience, and of bringing together all the sensations at the height of spring. But those experiences were not to last long. Ignatyev committed suicide in 1914, two days after his wedding. From that moment the Ego-Futurist group collapsed."

Friday – 9 May

Konstantin Melnikov, Sonata of Sleep, 1929–30

You can hear wind, water, thunder, birdsong, Debussy.

From Miguel Monila Alarcón's book: "Konstantin Stepanovich Melnikov (b. Moscow 1890 – d. Moscow 1974), painter and architect, is considered the most important figure in Russian constructivist architecture. After the 1917 Revolution, he taught at the Vhutemas school, drawing up a new urban plan for Moscow and designing worker's clubs outside the city. Melnikov's wish was that revolutionary soviet social values could be expressed in his buildings, although at the same time he publicly defended on many occasions "the right and need for personal expression", which he claimed as the only source of "delicate design". His projects were unpredictable, unusual and ultra-original, described at times as "unreal and fantastic" , even though most of them were realised. Melnikov followed the path of the organic combination of space with simple volumetric form, thinking of his architecture as "transparent walls" and putting the facades in second place. In 1929-30, he planned his "Green City", a city of rest in the green area of Moscow, with the aim of rationalizing rest by means of the "rationalization of sleep" in socialist cities, and in "daily life". For this city, he conceived green areas with a forest, gardens and orchards, a zoo, a children's city and a public sector, with a train station-concert hall, "solar pavilion" and "sleeping quarters" (which were the rest blocks for the workers). These dormitories had to be built by a collective, bringing together the efforts of different specialists, amongst others architects, musicians and doctors. For Melnikov, sleep was a curative source, more important than food and air. He wanted to fit out the dormitories with hydromassage; thermal regulation of heat and cold by means of stone stoves; chemical regulation with the aroma of forests, spring and autumn; mechanical regulation with beds that rotated, rocked and vibrate and finally, sonic regulation by means of "the murmuring of leaves, the noise of the wind, the sound of a stream and similar sounds from nature" (including storms), all of which would be heard by placing special sound horns at opposite ends of the dormitories. These would also reproduce symphonies, readings and sound imitations. Melnikov planned to replace bothersome "pure noise" (showers, washbasins, neighbours, conversations, snoring...) with "organized noises" based on the principles of music. Melnikov named these "sleeping quarters", and their concerts "Sonatas of Sleep" (SONnaia SONata in Russian), taking the Russian root SON ("Sleep") and using the play on words to allude to the famous Claire de Lune Sonata (Lúnnaya Sonata) by Claude Debussy. In the end, this project was never realised, nor was his dream of creating "The Institute for the Transformation of Humankind". In 1937, Melnikov was labelled a "formalist" and removed from education and practice and, although he managed to survive the Stalinist purges, he was never rehabilitated and had to work as a portrait painter on commission until his death in 1974. For the reconstruction of this "Sonata of Sleep" the natural sounds that Melnikov refers to in his texts have been used; it also includes a musical fragment of the Claire de Lune Sonata by Debussy, recorded in 1916 on a mechanical Piano Roll. With this project, we can consider Melnikov as an antecedent of "acoustic design", and also of the concepts of "sound ecology" and "sound landscape" which appeared again in the '70s."

Monday – 12 May

Dziga Vertov, Radio-Ear / Radio-Pravda, 1925

You can hear a train, a cuckoo, announcers, screaming, steam engines, singing, tapping, humming.

From Miguel Monila Alarcón's book: "In Dziga Vertov's ambition to "explore life", the latest technical inventions arising from the industrial revolution were employed with the intention both of "discovering and revealing the truth", and placing a revolutionary weapon in the hands of the workers. All this led him to create the Kino-eye ("what the eye cannot see"), Radio-Pravda (or "radio-truth") and Radio-ear ("I hear"). Through radio, he attempted to establish auditory communication across the whole of the world's proletariat by way of recording the sounds of workplaces and of life itself, captured without preparation (a kind of 'factory of facts'). These would subsequently be broadcast across a network of radio stations, making possible the mutual "listening" and "understanding" of all workers, regardless of their cultural origins. All these ideas were expressed in his manifesto "Radio-Pravda" (1925):

We defend agitation by facts, not only concerning sight, but also and in the same measure, concerning hearing. How could we establish an auditory relationship across the whole frontline of the world's proletariat? (...) Once organised and set-up, the presentation of any sound recording may easily be broadcast in the form of Radiopravda. It is therefore possible to establish, in all the radio stations, a proportion of radio-dramas, radio-concerts and news 'taken directly from the life of the peoples of different countries. Something that acquires fundamental importance for radio is the 'radio-journal - free of paper and distance (Lenin) - rather than broadcasting Carmen, Rigoletto, romances, etc., with which our radio-broadcasting began. (...) Against 'artistic cinema', we oppose Kino-Pravda and Kino-eye; against 'artistic broadcasting', we oppose Radio-Pravda and Radio-Ear. (...) And it will not be through opera or theatre representations that we will prepare. We will be intensely ready to offer proletarians from all countries the possibility of seeing and hearing the whole of the world in an organised manner. Of being mutually seen, heard and understood."

Dziga Vertov was not heard in his day and was not able to put these ideas into practice, although in 1925 he did make a silent film: "Radio Pravda" (n° 23 in the series "Kino-Pravda" Newsreel) of which less that a third has been preserved, showing, in a didactic way, the potential of the new medium, and his interest in using it - or perhaps in moving into it? It would be necessary to wait a few more years for his film "Enthusiasm! The Dombass Symphony" (1930) when these ideas would finally be realised – in this we see a radio tuning in to the Leningrad RV3 station to hear the sounds produced by the workers and by the mines and machinery of the industrial region of Dombass in the Eastern Ukraine. Vertov also uses sounds generated by radiophonic media itself and includes "the rhythm of a radio-telegraph" in some parts. All these sounds had been recorded on site, using a specially built mobile recording system (the "Shorin system") and subsequently edited – by cutting, on film, since there was no other means of sound editing available. For the radiophonic reconstruction of "Radio-Ear/Radio-Pravda", included in this recording, the sounds of the film were used and edited as a "factory of facts" to recreate the radiophonic project. Vertov's ultimate aim was to create a "Radio-Cinema Station of Sound Production and Recording" (recording and retransmission of sound images at a distance) in order to equal and surpass the technical and economic power of capitalism."

Tuesday – 13 May

Dziga Vertov, Laboratory of Hearing, 1916

You can hear crackle, wind, whispers, talking, machinery.

From Miguel Monila Alarcón's book: "Recreation of two "phonograms" (now lost) by the filmmaker Dziga Vertov. Conceived when he was still a teenager (before he encountered cinema, he studied piano and violin, and began writing poetry at the age of ten). With a Pathephone phonograph (model 1900 or 1910, acquired in St. Petersburg) Vertov recorded the sound of a waterfall and the buzz of a sawmill, transcribing them at the same time in words and letters in an attempt to create documentary compositions and musical-literary verbal assemblies directly to wax cylinders. According to Jonathan Dawson "for his studies of human perception (in 1916 Vertov enrolled in Petrograd Psychoneurological Institute) Vertov recorded and edited natural sounds in his Laboratory of Hearing, trying to create new forms of sound by means of the rhythmic grouping of phonetic units". In an interview in 1935 Vertov recalled: "I had the original idea of the need to enlarge our ability to organize sound; to listen not only to singing or violins - the usual repertoire of gramophone disks - but also to transcend the limits of ordinary music".

Wednesday – 14 May

Elena Guro, Finland, 1913

You can hear a voice, singing, reading, breathing.

From Miguel Monila Alarcón's book: "Elena Guro, pseudonym of Eleonora Genrikhovna von Notenberg (b. St. Petersburg 1877 - d. Ousikirkko, Finland 1913), was a painter, writer and poet who took part in the first demonstrations by the Russian futurist movement. She first participated with Nicolai Kulbin's group of impressionists, in 1910 breaking with him to found, along with her future husband Matiushin (musician and painter), the Union of Youth, a futurist group that in 1913 organized the opera "Victory over the Sun". In her early poetry she introduced words of "lyrical nonsense" anticipating some aspects of the later zaum language of the futurists. She was also a pioneer in her approach to nature and the organic world. As Matiushin said, "she opposes organism to mechanism" , attempting to recover the rhythm of nature. As she suggested: "Try to breathe the way the pines whisper in the distance, the way the wind passes disturbingly, the way the universe palpitates. Imitate the breathing of the earth and the phases of the clouds". This poem called "Finland" gets close to these ideas, including approaching, phonetically, the sound of conifer branches in Finland while recalling a person through those forest whispers. Her early death occurred on a summer trip to Ousikirkko (Finland) with Matiushin, Kruchenykh and Malevich in 1913, where they had gone to prepare the opera "Victory over the Sun". Later, in the 1920s, Mikhail Matiushin directed the "Department of Organic Culture" in the INCHUK, working on the concept of organic abstraction and the elementary forces of Nature - gathering their latent energies; a continuation of the ideas begun by his wife Elena Guro."

Thursday – 15 May

Alexander Mosolov, Zavod, Symphony of Machines - Steel Foundry, 1926–28

You can hear percussion, brass, strings, metal sheets.

From Miguel Monila Alarcón's book: "Alexander Vasilievich Mossolov (b. Kyiv Ukraine 1900 – d. Moscow 1973), a Russian avant-garde composer considered part of the current of constructivist and machinist music. During the revolutionary period, 1917-1918, he worked in the office of the People's Commissioner for State Control and even had some brief personal contact with Lenin. In 1920, he worked as a pianist for silent films and later was conductor of chamber music for the Association of Contemporary Music and a radio music editor. For the celebration of the tenth Anniversary of the October Revolution in 1927, he composed his most famous orchestral work: "Zavod. Symphony of Machines - Steel Foundry", a movement from the ballet "Steel" (1926-28), which was written to glorify the era of Soviet industrialisation in which "the machine symbolised power and reality: its beauty, the attraction of things objective and inexorable" (Manfred Kelkel). What was radically new in this work was the inclusion of a part written for 'metal sheet' to reflect the noise and clatter of the factory machines, lending the overall work a "barbaric style" - as well as 14 "ostinato variations" on a one-bar theme and an extreme concentration of "machine rhythms". It was performed throughout the world (Berlin, Liège, Vienna, the USA, and Paris) and it was at this time, in around 1931, that a recording was made and released on a 10" light-blue-label Columbia disc, by the Paris Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Julius Ehrlich, from which the recording included here is taken. This success abroad contrasted with the persecution Mossolov's works suffered after 1927 at the hands of the Association of Proletarian Musicians (RAPM), representing Stalinism in music. His works were considered "naturalistic" and "decadent", his music contributing to "public drunkenness". He was expelled from the Association of Contemporary Music in 1936 and condemned for making "anti-soviet propaganda", then arrested and sent to labour camps (GULAG) for eight years. Mossolov wrote a letter to Stalin, saying he had been made into "a kind of musical outlaw" when really he was "a loyal Soviet man". Still he wasn't freed until 1938, after which time he devoted himself to composing and researching the music of Russian and Oriental folksongs. The authorities continued to refuse to allow his works to be performed in public."

Friday – 16 May

Arseny Avraamov, Symphony of Sirens, 1922

You can hear explosions, sirens, fireworks, engines, bells, voices, planes, foghorns, whistles.

From Miguel Monila Alarcón's book: "Arseny Avraamov, pseudonym of Arseny Mikhaylovich Krasnokutsky (b. Novocherkassk/Rostov 1886 – d. Moscow 1944), was a composer, music theorist, performance-instigator and commissar for the arts in Narkompros (the People's Commissariat for Education) just after the Revolution, and helped set up Proletkult – encouraging the development of a distinctly proletarian art and literature. As a musician, he was involved in the debates on microtonality and in the 1920s, proposed to the People's Commissar for Education (Lunacharsky) an order to burn all pianos, because he considered the piano to be symbolic of the well-tempered system of tuning (popularised by Bach), which mutilates people's and composers' musical sense. His later experiments with "drawn sound film" (or "synthetic sound") led, in the early 1930s, to the creation of the first synthesised sound recording on film. Some years before, Avraamov, in his article Upcoming Science of Music and the New Era in the History of Music (1916), had predicted synthesised music and outlined his point of view on the future of the Art of Music thus: "Knowing the way to record the most complex sound textures by means of a phonograph – after analysis of the curve structure of the sound groove directing the needle of the resonating membrane – one can create synthetically any, even the most fantastic sounds by forming a groove with the appropriate structure of shape and depth."

He directed an International Musical Exhibition (Frankfurt) on the new technological advances in music, together with Leon Theremin and other exceptional musicians and researchers. He also investigated the poetic structures of Imaginists Sergei Esenin and Anatoly Mariengof (book Imazhinisty, 1921). As part of his desire to remind the proletariat of their true role – their power to decide their own history – Avraamov conceived a monumental proletarian musical work for the creation of which he would use only sounds taken directly from factories and machines. To this end, he organised several monumental concerts, which he called Symphony of Sirens (Симфония Гудков), inspired by the nocturnal spectacles of Petrograd (May 1918) and by the texts of Gastef and Mayakovsky. He eventually took these concerts to a number of Soviet cities celebrating the anniversaries of the October Revolution: Nizhny Novgorov (1919), Rostov (1921), Baku (1922) and finally Moscow (1923).

The most impressive and elaborate of these concerts was held on 7 November 1922 in the harbour of Baku in Azerbaijan. For this, Avraamov worked with choirs thousands strong, foghorns from the entire Caspian flotilla, two artillery batteries, several full infantry regiments, hydroplanes, twenty-five steam locomotives and whistles and all the factory sirens in the city. He also invented a number of portable devices, which he called "Steam Whistle Machines" for this event, consisting of an ensemble of 20 to 25 sirens tuned to the notes of The Internationale. He conducted the symphony himself from a specially built tower, using signalling flags directed simultaneously toward the oil flotilla, the trains at the station, the shipyards, the transport vehicles and the workers' choirs. Avraamov did not want spectators, but intended the active participation of everybody in the development of the work through their exclamations and singing, all united with the same revolutionary will. Avraamov reflected on the potential of music, and the influence of the sounds that define our environment – their importance and the role they had to fulfil after the October Revolution – an aspect of his thinking which helps us to understand the ultimate meaning of the composition of the Symphony of Sirens:

"Music has, among all the arts, the highest power of social organisation. The most ancient myths prove that mankind is fully aware of that power (...) Collective work, from farming to the military, is inconceivable without songs and music. One may even think that the high degree of organisation in factory work under capitalism might have ended up creating a respectable form of music organisation. However, we had to arrive at the October Revolution to achieve the concept of the Symphony of Sirens. The Capitalist system gives rise to anarchic tendencies. Its fear of seeing workers marching in unity prevents its music being developed in freedom. Every morning, a chaotic industrial roar gags the people.(...) But then the revolution arrived. Suddenly, in the evening - an unforgettable evening – a Red Petersburg was filled with many thousands of sounds: sirens, whistles and alarms. In response, thousands of army lorries crossed the city loaded with soldiers firing their guns in the air. (...) At that extraordinary moment, the happy chaos should have had the possibility of being redirected by a single power able to replace the songs of alarms with the victorious anthem of The Internationale. The Great October Revolution! – once again, sirens and cannon work in the whole of Russia without a single voice unifying their organisation."

This recording was made taking close note of Avraamov's instructions, originally published in Turkish in Baku's three local newspapers on 6 November 1922, the day before the event:

On the Fifth Anniversary of the October Revolution Instructions for the Symphony of Sirens:

On the morning of the Fifth Anniversary, on 7th November, all the ships from Gocasp, Voenflat, and Uzbekcasp, including all small boats and vessels, will gather near the dock of the railway station at 7:00 a.m. All boats will receive written instructions from a group of musicians. After that, they will proceed to occupy the place assigned to them near the customs dock. The destroyer Dostoyny, with the steam whistling machine and the small boats, will be anchored further up, in front of the tower.

-At 9:00 a.m., the whole flotilla will be in position. All the mobile machines, local trains, battleships and repaired steam machines will arrive at the same time. The cadets from the courses of the Fourth Regiment, the students from the Azgo Conservatory, and all the professional musicians will be on the dock no later than 8:30 a.m.

-At 10:00 a.m., the troops, the artillery, the machine guns, and the rest of the vehicles will also get into position, following the orders received. Airplanes and hydroplanes will also be ready.

-No later than 10:30, those in charge of making the signals will take their positions at the regional and railway terminals.

-The midday cannon has been cancelled.

-The squad in charge of the fireworks will give the signal to the following vehicles for their approach to the centre with the minimum possible noise: Zykh, Bely Gorod, Bibi, Abot and Babylon.

-The fifth shot will give the signal to the first and second district of the Black Quarter.

-The tenth shot, to the sirens of the commercial offices, of Azneft, and of the docks.

-The fifteenth shot, the districts, planes taking-off. The bells.

-The eighteenth shot, the sirens of the square and the steam machines located there. Simultaneously, the first company of the Military Academy will move from the square to the docks playing the march "Varashavanka".

-All the sirens sound and end at the twenty-fifth cannon shot.

-Pause.

-The triple chord of the sirens will be accompanied by a "Hurrah" from the docks.

-The steam whistling machine will give the final sign.

- "The Internationale" (four times). In the middle, a wind orchestra plays "La Marseillese" in combination with a choir of automobiles.

-The whole square joins singing in the second repetition.

-At the end of the fourth verse, the cadets and the infantry return to the square where they are greeted with a "Hurrah".

-At the end, a festive and universal choir with all the sirens and alarm signals plays for three minutes accompanied by the bells.

-The signal for the end is given by the steam whistling machine.

-Ceremonial march. Artillery, fleet, vehicles and machine guns receive their signals directly from the conductor on the tower. The red and white flag, is used for the batteries; the blue and yellow, for the sirens; a four-coloured red flag for machine guns, and a red flag for the individual interventions of boats, trains, and the automobile choir. At a signal of the battery, "The Internationale" is repeated twice throughout the final procession. The fire of the engines will have to be stoked for as long as the signals are maintained.

All the above instructions are directed to the high level ranks and for their irrevocable execution under the responsibility of its authorities: military, Azneft, Gocasp, and related educational institutions. All participants must have with them their respective instructions during the celebrations

Monday – 19 May

Nikolai Foregger & His Orchestra of Noises, Mechanical Dances, 1923

You can hear whistles, gongs, metal, drums, voices, chains.

From Miguel Monila Alarcón's book: "Nikolai Foregger, real name Nikolai Mikhaylovich Foregger (b. Moscow 1892 - d. Kuibyshev/Moldavia 1939) was a playwright and choreographer who in 1921, founded the MastFor (MASTerkaya FOReggera = Foregger Workshop) emphasizing a new system of dance and physical training called TePhyTrenage, which conceived of "the body of the dancer as a machine, and the muscles of volition as the machinist". They performed dances imitating a transmission chain or chain-saw, accompanied - behind the scenes - by an Orchestra of Noises, or Noise Orchestra (Шумовому Оркестру) which included broken glasses in boxes, shaken; different metal and wood objects, struck; packing boxes, drums, gongs, cheap whistles and shouting. The MastFor received negative official Soviet reviews and, following the destruction of his workplace in a fire of unknown origins, disappeared in 1924".

Tuesday – 20 May

Arseny Avraamov, The March of the Worker's Funeral, 1923

You can hear sirens, voices, horns.

From Miguel Monila Alarcón's book: "After the successful experience of the Symphony of Sirens in Baku, Avraamov was called by the Proletkult of Moscow to repeat this event for the celebrations of the Sixth Anniversary of the October Revolution (1923). In order to carry this out, they counted on the aid of the Metal Workers Union, the Factory Committees of the District of Transriver, the Young Communist Union, the Railroad Transports Commissariat, professional musicians of the Conservatory of Moscow and the Revolutionary Army of the Republic (RVSR). The result was not as expected: the long distances between the different sound elements prevented the creation of acoustic unity and the sirens version of "The Internationale" became incomprehensible for most listeners. New musical themes were included, like "The March of the Worker's Funeral" by an unknown composer, which used to be sung after "The Internationale" as a tribute to the workers who died in the revolution. This was the last time Avraamov's project was attempted. In 1924, a year later, Lenin died."

Wednesday – 21 May

Dziga Vertov, ENTHUSIASM!: The Donbas Symphony, 1930

You can hear crackling, an orchestra, bells, cuckoo clock, religious singing, voices, radio announcer, metronome, a bassoon, steam, a workers' band, revolutionary songs, drums, factory horns, trains, conveyer-belts, footsteps, accordion music.

From Miguel Monila Alarcón's book: "Denis Arkadievitch Kaufman (b. Bialyskov, Poland 1986 - d. Moscow 1954) adopted the name Dziga Vertov as an adolescent; a futurist pseudonym loosely translated as "spinning top". He studied piano, violin and psycho-neurology, at the same time writing poetry and recording natural sounds with a phonograph for his "Laboratory of Hearing" (1916). By 1918, he had begun to work with cinema and - with his future wife Elisaveta Svilova - created the group 'Kinoks' ("Kino-Eye"). Concentrating on documentary films, they championed "what the eye doesn't see". Between 1925 and 1929, he developed the idea of "Radio-Pravda" ("Radio-Truth") and "Radio-Ear" (from "I hear"). With the beginning of sound cinema (1929-30), he began at once to apply his ideas on the importance of sound, imagining his new film as a "sound and visual documentary". The first difficulty he encountered was how to record sound in exterior locations since no adequate technology existed at the time. To solve this problem, he turned to the staff in the laboratory run by Dr. Shorin, a scientist and inventor who had created the first "cinematic sound" system in Russia. From them he commissioned the construction of the world's first-ever mobile "sound recording station" (Vertov believed that the microphone should be able also to "walk" and "run"). Once built, Vertov launched what he called an "assault on sounds" in the Ukranian industrial complex of the Dombass coal mines[, occupied by the Russian Federation since 2014].

This recording work was not only "cerebral" but also "muscular", since the equipment weighed about 2800 pounds and there were no available means of transport. Vertov said that to capture the sounds they worked "in an environment of din and clanging, amidst fire and iron, through factory workshops vibrating with sound", getting all the equipment onto trains and descending into the mines. Some of the recordings turned out to be defective as a result of the excessive physical vibration experienced during takes, and it became necessary to modify the original plan for the film's final edit. Although there was no sound-editing table and although the sounds were recorded onto the same track as the images, Vertov didn't settle for having the picture synched with the sound. He wanted to create a "complex interaction between sound and image", and worked over "fifty days and fifty nights under maximum tension", to combine and re-arrange the industrial sounds and the shouts and songs of the miners as they struggled to achieve the production challenges of the Five Year Plan - the film's theme.

The score, co-written by Vertov and the composer Timofeyev, sometimes simultaneously brings together musical writing and the roar of motor noise, in the same way that the composer Alexander Mossolov did when he introduced a 'metal sheet' into the score of his orchestral work Zavod, Symphony of the Machines - Steel Foundry (1926-28, see above). After its premiere, the film was criticized for a number of reasons, above all for its anti-academic approach to the treatment of music. According to Vertov, "everything which is not 'sharp' or 'flat', in a word, everything which does not 'do-re-mi-fa-so-lize' was unconditionally labelled 'cacophony' by the critics. Indeed, the film was variously called "anti-formalist", "anti-newsreel" or "anti-film"; a "theory of caterwauling" was proposed, the film's soundtrack being described as a "Concert of Caterwauling". In contrast, the film was considerably better appreciated in the west. After a screening in 1931, Charlie Chaplin said "I would never have believed it possible to assemble mechanical noises to create suct beauty. One of the most superb symphonies I have known. Dziga Vertov is a musician"."

I'm interested also in how the film is about the act of listening. Towards the start of the film, we see someone put on head phone, to tune into the events in what follows. Spires of churches are topple; she listens in. Shots of telegraph poles and masts intermittently follow.

Thursday – 22 May

Yuliy Meitus, Dnieprostroi Dnieper (Water Power Station), 1930

You can hear crackling, drums, brass, xylophone.

From Miguel Monila Alarcón's book: "Yuliy Serhiyovych Meitus (Ukrainian: Юлій Сергійович Мейтус; 28 January 1903, Yelysavethrad – 2 April 1997, Kyiv), was a pianist in the First Cavalry and between 1923-24 of the Kharkov Opera Theatre and manager of the music section of the Proletcult Theatre. In 1920, he composed a work dedicated to the building of the Dnieper Hydro-Electric Power Station – an enormous 167 ft. high dam regulating the 1,400 mile long river Dnieper in Ukraine. At the time, it was the largest hydro-electric plant in Europe and the pride of the then Soviet state. Meitus composed his musical tribute between 1929-30, in parallel with the building of the dam itself, using percussion to portray the different stages of construction: commencement, excavation of the foundations, installation of the pylons, and completion. The musical language is close to a constructivist aesthetic, which had won an architectural prize for its constructivist design. The historic recording included here is the B-side of the Mossolov Columbia record, probably made in 1931 - a year after the work's composition." n.b.: On 22 March 2024, the dam and its power station was struck by eight missiles launched by Russia as part of a massive attack on energy infrastructure across Ukraine. Then on 12 April 2024, the dam caught on fire as a result of drone strikes launched by Russia. The fire caused around half a tonne of oil products leaking into the Dnieper River. The facility was again left in a "critical state" following another Russian attack on 1 June.

Monday – 26 May

Dmitri Shostakovich, Radio Message, 1942

You can hear voice, orchestral instruments.

From Miguel Monila Alarcón's book: On August 9, 1942, Dmitri Shostakovich's Symphony No. 7, known as the "Leningrad", was performed in the city of Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) in the middle of the Nazi siege. Musicians were collected from various locations along the front and Karl Eliasberg, then ill with dystrophy, conducted the Radio Leningrad Orchestra in the Great Hall of the Philharmonic Society. In order to ensure that the concert would not be interrupted, all points of enemy fire were neutralized and all Soviet canons remained silent for the duration of the performance, although more than one bomb and fascist projectile was still heard. The concert became "a symbol of the strength of spirit and resolve of the city's defenders".

Thursday – 29 May

Aleksei Kruchonykh, Mikhail Matyushin, Velimir Khlebnikov, Kazimir Malevich, Victory over the Sun, 1913

You can hear keyboards, brass, voices, whistles, an engine, plates and cutlery, purring.

From Miguel Monila Alarcón's book: "Victory over the Sun, the first futurist opera, was performed on December 3 and 5, 1913 at the Luna Park Theatre in St. Petersburg, with a libretto by Alexei Kruchenykh, prologue by Velimir Khlebnikov, music by Mikhail Matiushin and sets and costumes by Kazimir Malevich. This opera was considered as a work of "total art", a "theatre of integration", it was one of the first examples of "performance art" and "multidisciplinary collaboration". The aim of Victory over the Sun was none other than a "Victory over the Past" which, in Matiushin's words, is "the victory over the ancient, deep rooted concept that the Sun equals beauty", a world-illusion represented by "old romanticism and empty charlatanism". The opera follows a band of "Futurecountrymen" who set out to conquer the Sun with the Aviator as their new futurist hero. He, defeating gravity, manages to conquer it. That is why for the author of the text, Kruchenykh, "The basic theme of the opera is a defence of technology, in particular of aviation, and the victory of technology over cosmic forces and over biologism" - which at that time was represented by Symbolism. The opera was proposed by the Union of Youth who wanted to show the "First Futurist Theatre" but who, after paying large sums of money for the hire of the theatre and the production, ran into financial difficulties with the result that they had to do without an orchestra. The composer, Mikhail Matiushin, then only had a broken out of tune piano - supplied on the day of the performance - and a chorus of seven people, three of whom could actually sing.

On stage, Matiushin also added noises, such as rifle shots, propeller sounds, machine noises and the "unusual sound" of a plane crashing. For the musical parts, we have only 27 bars in which, on the one hand, Matiushin takes his inspiration from folk songs, and on the other, he tends to break with tonality, introducing harmonic dissonances and quarter-tones. Malevich encountered similar constraints with the staging and costumes, so the sets were curtains painted with geometric forms and no perspective and the costumes were made from cardboard and iron thread in simplified cubic, cylindrical and conical shapes. The stage and the figures had to be painted in black and white because there were no coloured varnishes, but this inconvenience was compensated for by the Luna Park Theatre's mobile lighting system, one of the first of its kind in the world, which could be used to create innovative visual effects - a kind of "pictorial stereometry" - by decomposing the figures with spotlights, depending on whether it lit hands, feet or heads.

The libretto, written by Alexei Kruchenykh, in places introduced a new language for the future which destroyed the laws of syntax: Zaum (language of the "beyond-mind"), which he and Khlebnikov invented and which is impossible to translate. He advised the actors to read this in a breathless way "with a pause after every syllable". The opera is composed of 2 acts in 6 scenes with a prologue written by Khlebnikov, which he was supposed to have read himself before the opera began, but because of his shyness, Kruchenykh read it instead. Act 1 deals with the arrest of the Sun, and includes the "Bully's song", a sound poem with one comprehensible line: "Keep your arms before dinner, after dinner and while eating buckwheat mush". Act 2 deals with life in the "Tenth Land of the Future" once the Sun has been removed, and includes the song "Petite Bourgeoisie" (a manifesto of struggle against petite bourgeoisie in the field of art). The act ends with a triumphant "Military song" by the Aviator in zaum using only consonants. According to witnesses, the opening night of the opera was the scene of a great scandal, with half the theatre shouting "Down with the Futurists!" and the other half "Down with the Scandalists!" When the audience demanded the author come on stage, Folkin, the theatre director, announced from the box: "They've taken him to the lunatic asylum!".

Monday – 2 June

Sergei Prokofiev and Georgi Yakoulov, "Factory" from the ballet Le Pas d'Acier, 1925–27

You can hear orchestra strings, brass, machinery.

From Miguel Monila Alarcón's book: "The musician Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev (b. Sontsovka/Ukraine 1891 - d. Moscow 1953) and the painter Georgi Yakoulov, pseudonym of Georgi Bogdanovich Yakoulian (b. Tiflis/Georgia 1884 - d. Erevan/Armenia 1928), collaborated on the ballet Le Pas d'Acier ("The Steel Step"), a commission by Serge Diaghilev with choreography by Leonide Massine, premiered in Paris by the Ballet Russe. The ballet's intention was, in the words of André Lischké, to gather up "the Soviet achievements during the period of war communism, exalting the social structures of the new regime, along with work in the factories, the power of machines and the love that flowered in that setting". When Prokofiev heard this proposal he was surprised: "I couldn't believe what I was hearing, It seemed to me that a window had opened and the fresh air that Lunacharsky spoke of was blowing in", especially when he had hopes of returning to Russia. The ballet is made up of two scenes, where the characters (dancers) express their social position through physical attitudes and mime: sailors, peddlers, an orator, a young female worker, policemen, thieves and small shopkeepers. Prokofiev composed the music between 1925-26, and Georgi Yakoulov designed the sets where, for numbers 9 and 10 of the score called L'Usine ("Factory") and Les Marteaux ("The Hammers"), he made a constructivist mobile setting with ladders, platforms, turning wheels, luminous signs and hammers of different sizes in which all the elements were put in motion while different workers on the platform beat out the rhythm with loud hammer blows.

In the second scene - in the factory - the noises generated by the set mingled with those of the orchestra while at the same time a duet was performed by the young female worker and the sailor (who had become a worker when he met her) consisting of a pantomime. It was premiered in Paris on June 7, 1927, to good audience response, but the reaction of both Russian émigrés and the Soviet commissars was negative. For the émigrés the work was a "Thorny flower of Proletkult", and they accused Diaghilev of being a "Soviet propagandist". The commissars, on the other hand, criticised Prokofiev for his ambiguity in the second scene - in the factory - asking, is this "a capitalist factory, where the worker is slave, or a soviet factory, where the worker is the master?", questioning Pokofiev's interpretation. "If it's a Soviet factory, when and where did Prokofiev examine it? From 1918 to the present day he has been living abroad and came here for the first time in 1927". Prokofiev excused himself, replying "That is the concern of politics, not music, and therefore I will not reply". But even if the composer was not interested in politics, politics was interested in him, and when he decided to return to live in Russia many of his works were banned (including Le Pas d'Acier). The version included here is an experiment in which the supposed noises that would have been generated by the set have been mixed in with the orchestra in a hybrid attempt to get close to the actual sonorous effect produced in the historic performances, thus going beyond simple present-day interpretations in which only the musical score is heard."